Shakespeare and Statistics¶

Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Droeshout_portrait

Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Droeshout_portrait

Can art and science be combined? Natural language processing allows us to use the same statistical skills you might learn in a science class, such as counting up members of a population and looking at their distribution, to gain insight into the written word. Here’s an example of what you can do. Let’s consider the following question:

What are the top 20 phrases in Shakespeare’s Macbeth?¶

Normally when we study Shakespeare we critically read his plays and study the plot, characters, and themes. While this is definitely interesting and useful, we can gain very different insights by taking a multidisciplinary approach.

This is something we would probably never want to do if we had to do it by hand. Imagine getting out your clipboard, writing down every different word or phrase you come across and then counting how many times that same word or phrase reappears. Check out how quickly it can be done using Python code in this Jupyter notebook.

Loading the text¶

There are many public domain works available at Project Gutenberg. You can search or browse to find works that you are interested in analysing.

We are going to search for the play Macbeth by William Shakespeare. On the Download This eBook page we’ll copy the Plain Text UTF-8 link, then use the Requests Python library to download it into a variable called macbeth. We can then refer to it by using macbeth at any point from here on

text_link = 'http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1533/1533-0.txt'

import requests

r = requests.get(text_link) # get the online book file

r.encoding = 'utf-8' # specify the type of text encoding in the file

macbeth = r.text.split('***')[2] # get the part after the header

macbeth = macbeth.replace("’","'").replace("“",'"').replace("”",'"') # replace any 'smart quotes'

For example, we can just print out the first 1000 letters to see that we’ve grabbed the correct document.

print(macbeth[0:1000])

This etext was prepared by the PG Shakespeare Team,

a team of about twenty Project Gutenberg volunteers.

cover

MACBETH

by William Shakespeare

Contents

ACT I

Scene I. An open Place.

Scene II. A Camp near Forres.

Scene III. A heath.

Scene IV. Forres. A Room in the Palace.

Scene V. Inverness. A Room in Macbeth's Castle.

Scene VI. The same. Before the Castle.

Scene VII. The same. A Lobby in the Castle.

ACT II

Scene I. Inverness. Court within the Castle.

Scene II. The same.

Scene III. The same.

Scene IV. The same. Without the Castle.

ACT III

Scene I. Forres. A Room in the Palace.

Scene II. The same. Another Room in the Palace.

Scene III. The same. A Park or Lawn, with a gate leading to the Palace.

Scene IV. The same. A Room of state in the Palace.

Scene V. The heath.

Scene VI. Forres. A Room in the Palace.

ACT IV

Scene I. A dark Cave. In the middle, a Cauldron Boiling.

Scene II. Fife. A Room in Macduff's Castle.

Scene III.

Looks good! But that’s a lot of reading to do. And a lot of phrases to count and keep track of. Here’s where some Python libraries come into play.

Crunching the text¶

noun_phrases will grab groups of words that have been identified as phrases containing nouns. This isn’t always 100% correct. English can be a challenging language even for machines, and sometimes the files on Project Gutenberg contain errors that make it even harder, but it can usually do a pretty good job.

This code cell installs two Python libraries for natural language processing, textblob and nltk, then downloads a corpora data file that will allow us to process the text.

This may take a while to run. On the left you will see In [*]: while it is running. Once it finishes you should see the output printed on the screen.

!pip install textblob --user

!pip install nltk --user

import nltk

try:

nltk.data.find('tokenizers/punkt')

except LookupError:

nltk.download('punkt')

try:

nltk.data.find('tokenizers/brown')

except LookupError:

nltk.download('brown')

from textblob import TextBlob

macbeth_phrases = TextBlob(macbeth).noun_phrases

print(macbeth_phrases)

What you’re seeing is no longer raw text. It’s now a list of strings. How long is the list? Let’s find out. len is short for “length”, and it will tell you how many items are in any list.

len(macbeth_phrases)

Looks like we have over 3000 noun phrases. We don’t yet know how many of them are repeated.

Counting everything up¶

Here’s where this starts to look like a real science project! Let’s count the unique phrases and create a table of how many times they occur. They’ll be sorted from most to least frequent.

import pandas as pd

unique_texts = list(set(macbeth_phrases))

text_counts = {text: macbeth_phrases.count(text) for text in unique_texts}

sorted_texts = sorted(text_counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

macbeth_counts = pd.DataFrame(data=sorted_texts, columns=['text', 'count'])

macbeth_counts

There are a lot of them, so we’ll use .head(20) which means show the top twenty. In these lists, the first item is always number 0.

macbeth_counts.head(20)

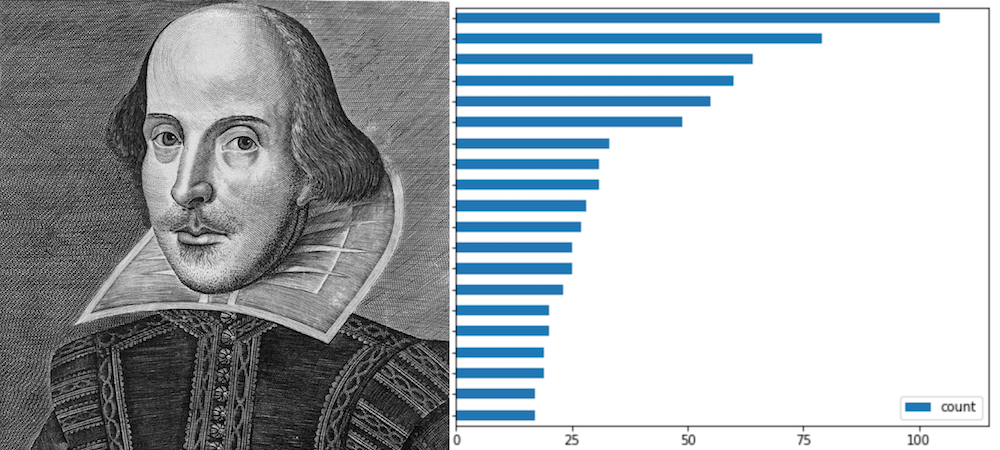

There we have it! The top 20 phrases in Macbeth! Let’s put those in a plot.

Plotting the results¶

You can do almost any kind of plot or other visual representation of observations like this you could think of in Callysto. We’ll use the cufflinks library to produce a horizontal bar plot, ordered from most to least frequent word.

import cufflinks as cf

cf.go_offline()

macbeth_counts_sorted = macbeth_counts.head(20).sort_values(by='count', ascending=True)

macbeth_counts_sorted.iplot(kind='barh', x='text', y='count', title='Phrase Frequencies in MacBeth', xTitle='Count')

Surprise, surprise. Macbeth is the top phrase in Macbeth. Our main character is mentioned more than twice the number of times as the next most frequent phrase, Macduff, and more than three times the frequency that Lady Macbeth is mentioned.

Thinking about the results¶

One of the first things we might realize from this simple investigation is the importance of proper nouns. Phrases containing the main characters occur far more frequently than other phrases, and the main character of the play is mentioned far more times than any other characters.

Are these observations particular to Macbeth? Or to Shakespeare’s plays? Or are they more universal?

Now that we’ve gone through Macbeth, how hard could it be to look at other texts?

Let’s define a function to to download an ebook from a text url, pull out all the noun phrases, count them up, and plot them. We can then use this for any ebook text that we would like to visualize.

def word_frequency_plot(text_url):

r = requests.get(text_url)

r.encoding = 'utf-8'

if 'gutenberg' in text_url:

text = r.text.split('***')[2]

else:

text = r.text

text = text.replace("’","'").replace("“",'"').replace("”",'"')

phrases = TextBlob(text).noun_phrases

unique_texts = list(set(phrases))

text_counts = {text: phrases.count(text) for text in unique_texts}

sorted_texts = sorted(text_counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

counts = pd.DataFrame(data=sorted_texts, columns=['text', 'count'])

counts_sorted = counts.head(20).sort_values(by='count', ascending=True)

counts_sorted.iplot(kind='barh', x='text', y='count', title='Phrase Frequencies', xTitle='Count')

print('Word frequency plot function defined.')

Looking at Hamlet¶

Hamlet can be found on Project Gutenberg under EBook-No. 1524.

Run the following code to download Hamlet, pull out all the noun phrases, count them up, and plot them out.

word_frequency_plot('http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1524/1524-0.txt')

Conclusion¶

Now that we have a function to plot word frequency, you can try this with other ebooks from Project Gutenberg. You could also try running this on news articles or any other text, although there may be some tweaks required.

However this example is only scratching the surface of natural language processing. Libraries such as spaCy can be used to identify parts of speech, vaderSentiment can categorize text based on its tone, and textstat can check the readability and complexity of text. Examples can be found here.

You could use these libraries to compare different writers or different times in history, see if you can trends in sentiment or word usage, or investigate changes in language and style.