%%html

<script>

function code_toggle() {

if (code_shown){

$('div.input').hide('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Show Code')

} else {

$('div.input').show('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Hide Code')

}

code_shown = !code_shown

}

$( document ).ready(function(){

code_shown=false;

$('div.input').hide()

});

</script>

<p> Code is hidden for ease of viewing. Click the Show/Hide button to see. </>

<form action="javascript:code_toggle()"><input type="submit" id="toggleButton" value="Show Code"></form>

Music - Mathematics of Pitch¶

There are many connections between mathematics and music, ranging from how rhythms fit together, to how notes fit together in chords, to the structure of counterpoint, and more.

We will focus on the connection between the pitch of notes and fractions. We will see that the idea of harmonious notes is closely connected to simplicity in fractions. We will also look at how a problem with these fractions was solved in the Baroque period by creating a well-tempered scale that made singers and instruments sound harmonious in all possible key signatures.

%matplotlib inline

from matplotlib.pyplot import *

from numpy import * ## for numerical functions

from math import tau

from IPython.display import Audio, display, HTML ## to output audio

from ipywidgets import interact, RadioButtons

Outline¶

A quick overview of what will be covered in this notebook.

First, we test the sound system on your computer

Then we briefly discuss some of the characteristics of musical notes, including:

loudness

duration

pitch

timbre

envelope

We then look at the history of finding notes in a scale, using simple fractions

The Circle of Fifths method is discussed

We then look at the well-tempered tuning, which solved an important problem for musicians.

Throughout we will use code to generate synthetic sounds on the computer to demonstrate many of these ideas.

Setting up¶

This notebook will play sound through the speakers or headphones of your computer. To make sure this works, try clicking on the arrow of the audio icon below. You should hear some random noise.

If you don’t hear any sound at all, or it’s too loud, try adjusting the volume and making sure that the audio devices are activated on your computer.

Once you can get sound from the audio icon below, please continue to the notebook content below.

Fs = 44100

random_sd = random.randn(Fs)

display("Click on the arrow to test sound. ")

Audio(data=random_sd, rate=Fs)

'Click on the arrow to test sound. '

Notes of the musical scale¶

Music is make up of individual sounds often referred to as “notes”. In the movie “The Sound of Music,” the children are taught a song that names the individual notes, as in these lyrics:

Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do

Doe, a deer, a female deer

Ray, a drop of golden sun

Me, a name I call myself

Far, a long, long way to run

Sew, a needle pulling thread

La, a note to follow Sew

Tea, a drink with jam and bread

That will bring us back to Doe.

If you haven’t seen the movie, here is a clip from YouTube:

%%html

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/pLm07s8fnzM" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The note names Do, Re, Mi, … were originally Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Si, … and came from a hymn in Latin, circa the year 1000. The first stanza is:

Ut queant laxis

resonare fibris,

Mira gestorum

famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti

labii reatum,

Sancte Iohannes.

and the first two letters of each line gave the names of the notes. Except for the initials SI in the last line, for Saint Iohannes. The word “Ut” was eventually replaced with “Do” for Dominus. (of course)

So there’s a little Latin for you!

Nowadays we usually refer to the notes in the scale by the letters C,D,E,F,G,A,B and return to C. These correspond to the white keys on the piano, while sharps and flats are the black keys.

Characteristics of notes in music¶

Notes have a number of characteristics, including the loudness, the duration, the pitch, timbre, and envelope. Perhaps you already know what these mean: certainly the loudness and duration, or length in time, should be clear. The pitch is basically whether a note sounds high (like a young child’s voice) or low (like a man’s voice). Timbre characterizes the difference between, say, a flute and an electric guitar, when the notes from the flute are very clean and pure sounding, while an electric guitar can sound harsh and rough. The envelope describes how the note evolves over time: does it have a sharp initial attack, is it sustained for a long period, does it decay slowly to silence or stop abruptly.

Here are five different examples of sounds which vary the individual characteristics of the notes: loudness, duration, pitch, timbre, and envelope. Real sounds of course can vary much more than these synthetic notes.

Click on the “Play” button (the arrow head) to hear each one.

def heaviDecay(t):

return heaviside(t,1)*exp(-t)

Fs = 44100

Len = 3

t = linspace(0,Len,Len*Fs)

freq = 261.6 # middle C

sineWave = sin(tau*freq*t)

intSteps = floor(1+4*t/Len)

varyLoudness = intSteps**2*sineWave

varyDuration = maximum(0,sin(tau*4*(t/Len)**2))**.5*sineWave

varyPitch = sin(tau*intSteps*freq*t)

varyTimbre = maximum(-1,minimum(1,intSteps**2*sineWave))

varyEnvelope = (heaviDecay(10*t)+heaviDecay(5*(t-1))+heaviDecay(t-2))*sineWave

a1=Audio(data=varyLoudness, rate=Fs)

a2=Audio(data=varyDuration, rate=Fs)

a3=Audio(data=varyPitch, rate=Fs)

a4=Audio(data=varyTimbre, rate=Fs)

a5=Audio(data=varyEnvelope, rate=Fs)

display("A sound with changing loudness.",a1,

"Several notes with changing duration.",a2,

"A sound with changing pitch.",a3,

"A sound with changing timbre",a4,

"Several notes with different envelopes.",a5)

'A sound with changing loudness.'

'Several notes with changing duration.'

'A sound with changing pitch.'

'A sound with changing timbre'

'Several notes with different envelopes.'

Sample notes¶

Of course, when creating a note, there is the possibility of changing any or all of these characteristics. For instance, by adjusting these there sliders, you can alter the pitch, timbre and envelope of a note and hear what it sounds like.

Try it out now: click on the sliders to move the buttons and hear the resulting sound.

## Code block E

Fs = 44100

Len3 = 3

t3 = linspace(0,Len3,Len3*Fs)

freq_c = 261.6 # middle C

sineWave = sin(tau*freq_c*t3)

intSteps = floor(1+4*t3/Len3)

run_e = 0

def play_e(pitch,timbre,envelope):

global run_e

if run_e == 0:

run_e = 1

return

data1 = heaviDecay(envelope*t3)*maximum(-1,minimum(1,timbre**2*sin(tau*pitch*t3)))

a1=Audio(data=data1, rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display(a1)

interact(play_e,pitch=(200,400),timbre=(1,5),envelope=(1,10));

Pitch and harmony¶

People in ancient civilizations noticed a long time ago that notes of certain pitches sound “good” together. We often say such notes sound harmonious. They also noticed that the pitch of sound produced by singers, or instruments, were somehow related to the size, shape and weight of the singer or instrument. For instance, a big man would typically sing in a low pitch, while a small woman or child would sing in a higher pitch. A large drum makes a deep, low sound while a small drum or wood block would make a high sound.

Pitch is related to the rate of vibration of an object producing sounds. Although the ancients could not measure this directly, certainly they would have noticed by touching their throats while singing, that a low-pitched sound has a slow vibration, and a high-pitched sound has a faster vibration.

We can now measure the frequency of notes, and discover that the range of human voices produce vibrations with frequency as low as 80 cycles per second (for a male bass singer) to as high as 1000 cycles per second (for a female soprano singer).

Try this out with the slide below. Perhaps you can sing along to some of the notes!

## Code block F

Fs = 44100

Len3 = 3

t3 = linspace(0,Len3,Len3*Fs)

run_f = 0

def play_f(pitch):

global run_f

if run_f == 0:

run_f = 1

return

a1=Audio(data=sin(tau*pitch*t3), rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display(a1)

interact(play_f,pitch=(80,1000));

Harmony and arithmetic¶

It was perhaps the ancient Greeks who first noticed a connection between harmonious notes and mathematics. They observed that strings of different lengths, but the same thickness and tension, would often produce harmonious pairs of tones if the string lengths were in the ratio of simple fractions. You may have noticed this yourself if you play a guitar or ukelele.

For instance, one string that was half the length of another would produce a note that was an octave higher that the other string. A string that was two-thirds the length would produce the C-to-G interval, which we now call “a fifth.”

The Greeks didn’t know it, but the frequency (or pitch) was directly related to the reciprocal of these fractions. So the string of one-half (1/2) length would have 2 times the frequency. The string of two-thirds (2/3) length would have three-halves (3/2) the frequency.

With this idea in mind, we can take a few fractions with a small denominator like 4, and get some really nice notes.

Indeed, the fractions 4/4, 5/4, 6/4, 7/8 and 8/4 correspond to frequencies of the main notes in a Boogie-Woogie chord. In our modern notation, these are the notes C,E,G,B-flat and the C an octave higher.

We can create these notes synthetically on the computer very easily. Try clicking on the controls below to hear these familiar notes. The relevant fraction is shown below, and is precisely the fraction we used to create the note.

## Codeblock A

Fs = 44100

Len05 = 0.5

t05 = linspace(0,Len05,int(Len05*Fs))

freq_c = 261.6 # middle C

notes_a = ['C (1)', 'E (5/4)', 'G (6/4)', 'B flat (7/4)','C (2)' ]

fracs_a = array([1,5/4,3/2,7/4,2])

run_a = 0

def play_a(Note):

global run_a

if run_a == 0:

run_a = 1

return

i = notes_a.index(Note)

frac = fracs_a[i]

a1=Audio(data=sin(frac*tau*freq_c*t05)*heaviDecay(4*t05), rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display(Note,a1)

interact(play_a,Note=RadioButtons(options=notes_a,value=notes_a[-1]));

Scales and fractions¶

We can go further and create the full scale from C to C, using the small fractions 1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, and 2. Granted, the fractions 9/8 and 15/8 stand out as a bit unusual, as they seem to have a pretty big denominator – but these are the fractions that give us the familiar Western scale.

Below, you can click on the radio buttons to see what those notes sound like.

## Codeblock B

Fs = 44100

Len05 = .5

t05 = linspace(0,Len05,int(Len05*Fs))

freq_c = 261.6 # middle C

notes_b = ['C (1)', 'D (9/8)', 'E (5/4)', 'F (4/3)', 'G (3/2)', 'A (5/3)', 'B (15/8)', 'C (2)' ]

fracs_b = array([1,9/8,5/4,4/3,3/2,5/3,15/8,16/8])

run_b = 0

def play_b(Note):

global run_b

if run_b == 0:

run_b = 1

return

i = notes_b.index(Note)

frac = fracs_b[i]

a1=Audio(data=sin(frac*tau*freq_c*t05)*heaviDecay(4*t05), rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display(Note,a1)

interact(play_b,Note=RadioButtons(options=notes_b,value=notes_b[-1]));

Out of tune¶

Do those notes sound right to you? If you are an experienced musician, they might seem a little off.

In fact, there is a problem with these notes. Although they are designed to be harmonious (as the ancient Greeks felt they are), there is a problem when a musician starts to transpose notes to different keys. The problem is when you shift all those fractions up by a fixed amount, the new frequencies don’t necessarily align with the old.

For instance, if we take the C scale and shift to the G scale, we should take the fractions 1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, … and multiply them all by 3/2 (making the base frequency 3/2). We end up with the fractions

Now, on the right-hand side, we see the familiar fractions 3/2, 15/8 and 2. But in the middle is that 27/16 where we should be expecting a 5/3, corresponding to the A in our scale. It is out of tune, by quite a bit, because

So this note might sound terribly out of tune.

Perhaps this is most easily illustrated with the Circle of Fifths idea.

Circle of Fifths¶

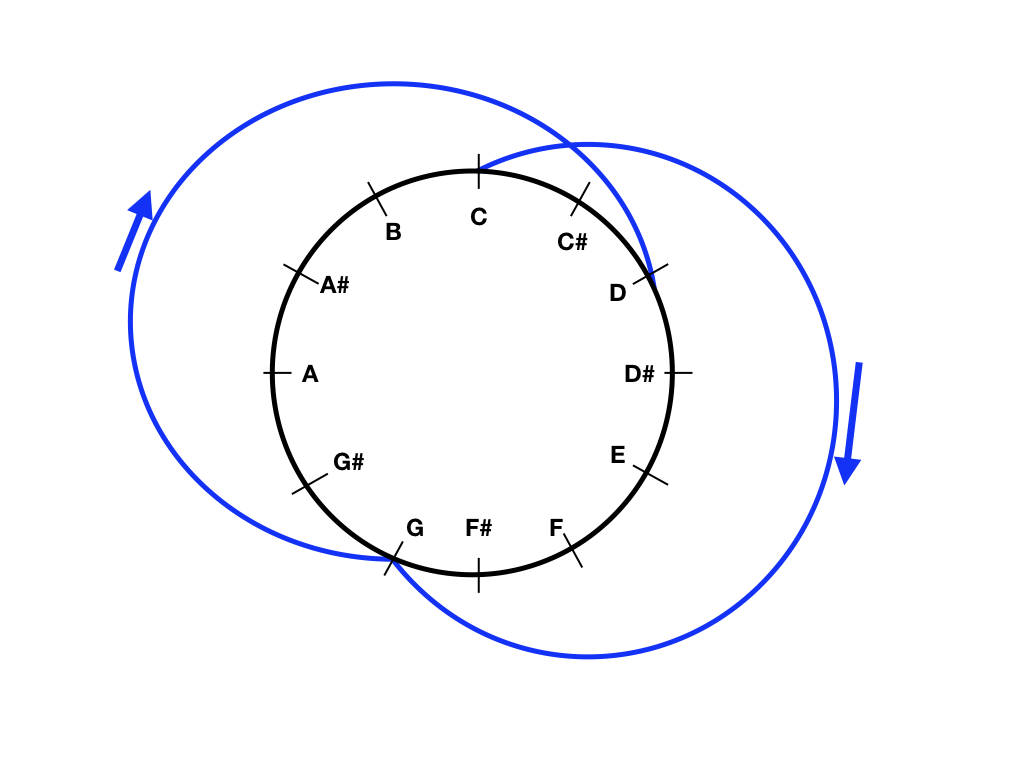

Here is an interesting method for creating the notes in our Western scales. The idea is that the interval C to G, can be used to generate all the notes in the Western tonal scale.

Graphically, we can look at the following picture, which lists all the notes C,D,E,F,G, A, and B, as well as the sharps that can occur. Note that sharps correspond to the black keys on the piano.

The interval from C to G is called a “fifth” in western music, because G is the fifth note in the usual diatonic scale that goes C,D,E,F,G,A,B,C. This fifth is marked on the above circle by the blue arc going from C to G.

We can also get from C to G on this circle by counting off “ticks” on the circle: it takes 7 ticks to go clockwise from C to G. Each tick corresponds to a semitone in music, so there are seven semitones in a fifth.

If you count another seven ticks from G, it will bring you past the C at the top of the circle and get you to D. This is marked by the second arc, going from G to D.

Exercise:¶

Continue this pattern. Count seven ticks clockwise from D, you should end up at A. Repeat the seven ticks: what comes after A? Then what comes after that?

Repeat this pattern. After a total of 12 repeats, you should come back to the beginning note. What is the sequence of notes generated by following the circle of fifths? (Note: We saw above that the sequence starts as C, G, D, A, …)

Did you notice that the sharp notes all come at the end of the sequence? Why is that?

Draw your own circle of fifths, and include all 12 arcs that move you across all the notes in the circle.

The Circle of Fourths. The interval C to F is called a fourth, and consists of 5 semitones (moving clockwise by 5 ticks on the circle). Check yourself that by moving through a fourth each time in the circle, you will eventually pass through every note on the circle.

Mathematics in the Circle of Fifths.¶

We discussed earlier that the jump from C to G corresponds to increasing the frequency of our note by a factor 3/2. This is true for any leap of a fifth: the frequencies increase by a factor of 3/2. So, if we think of 1 as our base frequency for C, then 3/2 is the frequency for G, and (3/2)x(3/2) = 9/4 should correspond to the note D.

But of course, this D is too high – it is an octave higher than what we want, so divide by 2 to bring it down an octave, to get (9/4)/2 = 9/8. This agrees with our fractional scales discussed above.

To go from D to A, we again multiply by 3/2, so (9/8)x(3/2) = 27/16. This is not quite 5/3 = 1.66667 but pretty close, as 27/16 = 1.6875.

From A to E, we multiply again by 3/2 to get 81/32 and again this is too high by an octave, so we divide by 2 to get \(81/64 \approx 80/64 = 5/4.\)

We should be able to continue with these fractions to get all possible frequencies for the notes on the circle. Unfortunately, this is not quite right, as we will see in the next section.

Well-tempered tuning and roots of two¶

The problem with the fractional tuning is this Circle of Fifths doesn’t bring you back to C, exactly.

The math behind this is that each time you move by a fifth, the frequency will increase by exactly 3/2. So the frequencies increase like this pattern: \( 1, (3/2), (3/2)^2, (3/2)^3, \ldots, (3/2)^{12}.\) But we can compute (3/2)^{12} = 129.746. This is just a bit bigger than 128 = 2^7, which is a power of two. Remember, powers of 2 give us octave jumps. So the circle of fifth brings us to a note slightly higher than the C which is seven octaves higher.

This got to be such a problem for musicians that in Baroque period, various people proposed a “well-tempered” system of tuning for notes where the intervals for frequencies differences are given by powers of the number 2.

You may have heard of Bach’s composition “The Well Tempered Clavier” which is a collection of 24 pieces in all major and minor keys, demonstrating the utility of the well-tempering system.

%%html

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/ezZdbzreNcs" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Fixing the math¶

The basic idea in well-tempering is to choose an number close to 3/2 = 1.5 so that its twelfth power is exactly 128. In fact, we find \( 1.4983071^{12} = 128.\) Now when we go around the circle of fifths, we will come back exactly to C, in exact frequencies.

If you know a bit of algebra, you might recognize this number 1.4983071 as the 12-th root of 128.

Another way to describe the circle of fifths is to measure the size of the semitone. We need a number that solves \(x^{12} = 2\) which just says we need 12 semitones in an octave. The answer is the twelfth root of two, or approximately \( x= 1.0594631.\)

Now this has solved our problem with tuning. All our notes are related to each other by powers of 2. Shifting up and down the scale amounts to multiplying or dividing by some power of two, so every notes stays in the proper relationship to other notes. There are distinct 12 notes in this system. If we play them all, we get the chromatic scale which includes the notes

C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B, and back to C.

You might well ask, have we lost the exact harmony of the ancient Greeks? Well, indeed we have, but only approximately. See if you can hear the difference, by playing these well-tempered notes in the major C scale. Click on the radio buttons to hear the notes.

## Code block C

Fs = 44100

Len05 = .5

t05 = linspace(0,Len05,int(Len05*Fs))

freq_c = 261.6 # middle C

notes_c = ['C (1.0)', 'D (1.0595)^2', 'E (1.0595)^4', 'F (1.0595)^5', 'G (1.0595)^7', 'A (1.0595)^9', 'B (1.0595)^11', 'C (2.0)' ]

fracs_c = (2**(1/12))**(array([0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12]))

run_c = 0

def play_c(Note):

global run_c

if run_c == 0:

run_c = 1

return

i = notes_c.index(Note)

frac = fracs_c[i]

a1=Audio(data=sin(frac*tau*freq_c*t05)*heaviDecay(4*t05), rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display(Note,a1)

interact(play_c,Note=RadioButtons(options=notes_c,value=notes_c[-1]));

Side by side comparison¶

Here we have both the fractional scale, and the well-tempered scale.

Click on the radio buttons, to see if you can hear the difference. Notice the display shows the exact value of the fraction and the power of two. In all cases, the difference is less than a percent, which is very difficult to hear unless you are a trained musician. (The A and the E sort of stand out as quite different.)

## Code block G

Fs = 44100

Len05 = .5

t05 = linspace(0,Len05,int(Len05*Fs))

freq_c = 261.6 # middle C

notes_g = notes_b+notes_c

fracs_g = append(fracs_b,fracs_c)

run_g = 0

def play_g(Note):

global run_g

if run_g == 0:

run_g = 1

return

i = notes_g.index(Note)

frac = fracs_g[i]

a1=Audio(data=sin(frac*tau*freq_c*t05)*heaviDecay(4*t05), rate=Fs,autoplay=True)

display("Note "+Note,"Decimal value: {:.6f}".format(frac), a1)

interact(play_g,Note=RadioButtons(options=notes_g,value=notes_g[-1]));

Exercises¶

Compute the percentage difference between the values in the fractional scale, and in the well-tempered scale. Show that the notes A and E have large percentage differences. Find a third note that also has a rather large percentage different.

Can you use the well-tempered idea to create another scale, based on powers of another number? Can you pick a number that gives you something that sounds nice and harmonious. (Note you don’t necessarily need 12 notes in your scale.)

Can you make some some scales with notes using other small fractions, like 5/5, 6/5, 7/5, 8/5, 9/5, 10/5? Do these sound harmonious to you? What about fractions with denominators or 6 or 7?

Summary¶

Musical notes have many characteristics, and an important one is the pitch. Pitch is related to the frequency of vibrations for whatever is creating the sound. Human singers can sing notes with frequencies ranging from about 80 cycles per second, to 1000 cycles per second.

Scales for notes in Western music are based on the observation that notes of certain frequencies sound harmonious together. The key observation is that if the frequencies of the notes are in the ratio small integers (the fractions have a small numerator and denominator) then the notes often sound good together.

The C major scale (C,D,E,F,G,A,B,C) is given by frequencies in the ratios 1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, and 2. A major scale in any other key should have the same ratio of frequencies which are these small integers.

The Circle of Fifths shows us that these fractions cannot work out exactly. This becomes a problem for musicians who must play music in different keys, with various instruments. The solution was to create the well-tempered scale, where notes are related to each other by fractional powers of two.

Specifically, the well-tempered scale uses integer powers of \(2^{1/12} = 1.0594631\), where the 2 comes from the fact that an octave represents a doubling in frequency, and the 12 represents the 12 distinct, evenly scaled notes in the chromatic scale. Using this well-tempered method gives a very good approximation to the simple fractions that the ancient Greeks preferred, but still sounds good to our ears.