import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

import mpl_toolkits.mplot3d.axes3d as p3

from matplotlib import rc

from IPython.display import display, Math, Latex, HTML, clear_output, Markdown, IFrame, Javascript

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, FloatSlider, IntSlider, interactive, Layout

from traitlets import traitlets

from plotly.offline import download_plotlyjs, init_notebook_mode, plot, iplot

init_notebook_mode(connected=True)

%matplotlib notebook

#Convenience function that evaluates a certain cell range

def evaluate_cells(de, a):

display(Javascript('IPython.notebook.execute_cell_range(IPython.notebook.get_selected_index()+%s,IPython.notebook.get_selected_index()+%s)'%(de,a)))

return

HTML('''<script>

function code_toggle() {

if (code_shown){

$('div.input').hide('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Show Code')

} else {

$('div.input').show('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Hide Code')

}

code_shown = !code_shown

}

$( document ).ready(function(){

code_shown=false;

$('div.input').hide()

});

</script>

<form action="javascript:code_toggle()"><input type="submit" id="toggleButton" value="Show Code"></form>''')

The Nature of Thermal Energy¶

In this Jupyter Notebook you will explore the nature of thermal energy and its effects on different forms of matter using informal observations, experimental evidence, and models. By the end of the notebook you will have gained an understanding on:

comparing heat transmission in different materials

explaining how heat is transmitted by conduction, convection and radiation in solids, liquids and gases

describing the effect of heat on the motion of particles; and explain changes of state, using the particle model of matter

distinguishing between heat and temperature; and explain temperature, using the concept of kinetic energy and the particle model of matter

investigating and describing the effects of heating and cooling on the volume of different materials, and identify applications of these effects

Necessary Background: Basic understanding of kinetic energy and states of matter.

Thermal energy applications are found throughout our daily lives; the means by which a refrigerator functions, the ways we power and heat our homes, the combustion which drives our engines. These are just a few of the many ways we use thermal energy to improve our lives. Consequently, having a better understanding of the nature of thermal energy means having a better understanding of the world around us, natural and manufactured.

Heat vs. Temperature¶

The difference between temperature and heat is quite subtle. We’d better state the definitions formally:

Heat is a type of energy transfer in which energy flow is caused by a difference in temperature.

Temperature is a measure of the average heat or thermal energy of the particles in a substance.

These are simple explanations for the time being and will become clearer over the course of this notebook. heat is a microscopic quantity which gives rise to the macroscopic quantity of temperature. We often think of heat and temperature interchangeably but they have fundamentally different meanings. Heat can be exchanged between matter and temperature can be possessed by matter. Over the course of this notebook the differences will become clearer.

Side note: Macroscopic vs Microscopic

Macroscopic quantities can be thought of as the things that you can see and quantify, whereas microscopic quantities are the opposite of this; they need some more detailed measuring tools in order to observe. For example, consider the picture of a forest below. Many trees come together to make up the entire forest. In the picture, these trees are comprised of many different shades of green. As we zoom in further, we see that these shades are actually just individual square pixels, each with one colour and brightness. The brightness, colour, and size of each pixel can be seen as the microscopic properties. The macroscopic properties would be the individual trees and the forest that they form. Microscopic properties can only be seen as we zoom into the image. Similarly, macroscopic properties can only be seen as we zoom out.

Particle Model of Matter¶

In order to help you understand heat, it will be useful to think of the Particle Model of Matter. This model was first proposed by the Greek philosopher Democritus over 2000 years ago. He thought of being able to cut up matter, the stuff that makes up everything in the world, into smaller and smaller parts. Eventually, one would reach its basic components; the particles that make up all matter. The term particle is still used everywhere in the physical sciences. They can be simply thought of as small objects with certain properties such as size, speed, or colour. Typically they form interact together in terms of these properties, creating some macroscopic property. Using the concept of a particle has helped us model how different microscopic quantities combine to create macroscopic ones. The particle model states that:

1. All matter is made up of tiny particles¶

Place your mouse over the image below to interact.

%%html

<div style="text-align: center">

<iframe width="500px" height="420px" src="animations/cube_grid.html" frameborder="0"></iframe>

</div>

2. The particles are constantly moving¶

Since the particles are not at absolute (0 Kelvin), they still contain a bit of thermal energy. When the particles are bound in a solid structure, like above, this causes them to vibrate slightly. Particles in any state will always slightly unless they are at absolute 0 temperature. Below is the same solid as above, but depicted more realistically.

%%html

<div style="text-align: center">

<iframe width="450px" height="420px" src="animations/vibrating_cube.html" frameborder="0"></iframe>

</div>

Side Note: absolute Zero

The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale using 0 as the point where all motion due to heat. The celsius scale on the other hand uses the freezing point of water as its zero, which corresponds to 273.15 Kelvin. This can be inconvenient for many scientists, especially when quantities have to be multiplied by temperature, thus the Kelvin scale is the international standard and is recognized as the base unit of temperature. Absolute 0 is an absolute since all motion for any type of matter will stop at this temperature. That being said, absolute zero is actually physically impossible to reach Click here if you’re interested. There is ongoing research on cooling matter to extremely low temperatures in order to observe its behaviour when there is nearly zero thermal motion.

3. The particles move faster as you heat them up¶

%%html

<div style="text-align: center">

<iframe width="450px" height="420px" src="animations/particle_in_a_box.html" frameborder="0"></iframe>

</div>

Statement 3 of the particle model offers the clearest description for the difference between temperature and heat. As the temperature inside the square increases, the particles move faster. This is because the the particles have more heat energy, but what we actually measure is temperature. The particles collide with the sides of the box more frequently. The more frequent the collisions, the higher the temperature we measure. Above is a graphic describing how the ‘particles’ that make up water might behave as they are heated.

Changes of State¶

Heat transfer plays a deciding role in the changes of state of matter (Solid, Liquid or Gas). Let’s break down how heat energy changes the state of matter and what these processes are called. Matter will be thought of as a collection of particles. The behaviour of these particles is determined by the state of matter in which they are in:

Particles in a solid are tightly packed. They have very little motion other than vibrating in the location that they are in.

Particles in a liquid are able to move past one another. This is what gives liquids the property of being able to “flow”.

Particles in a gas can essentially move around freely, occasionally colliding into one another. This is why gases have so much free space.

Note the use of a macroscopic quantity to used to describe microscopic ones (state \(\rightarrow\) motion).

Why do the changes happen?¶

Matter changes state due to heat energy. Think of the particles in a solid. As they gain more heat energy, the particles themselves gain more kinetic energy. More kinetic energy means they are moving faster, making them collide into one another more often. Eventually the bonds that hold the solid together cannot maintain the amount of collisions and the solid begins to break apart, into a liquid. This is known as melting.

Once the matter has melted, the particles begin to flow, yet they still maintain a bit of their structure; they are still “connected”. If you were to give them even more heat energy, the structure begins to fall apart, and eventually the matter becomes a gas where the particles can move around freely and disperse from one another. This process is called evaporation.

Some of the main characteristics of a substance are the temperatures at which these transitions happen. These are known as the melting point and boiling point of the substance. For example, water has a melting point of 0\(^{\circ}\)C and a boiling point of 100\(^{\circ}\)C (STP) and these temperatures are a fundamental part of what it means to be “water”. The acronym SATP stands for Standard Ambient Temperature and Pressure, and is used as a standard ruler for experimental measurements. The melting and boiling points of water change at different pressures and therefore the pressure at which these quantities were measured must be specified as well. This allows for accurate comparisons between different experiments and laboratories.

The different changes that occur in matter are pictured below. Try to memorize the names of the different changes of state. Hover your mouse over each black box to see the names of them. Once you press the “Play memory game” button, you won’t be able to see their names anymore and will have to match the numbers to the name of change of state. See how many times you can get them correct! You’ll have them memorized in no time :-)

%matplotlib notebook

#Memory game for state transitions

import random

x = [470,550,810,810,1100,1180]

y = [550,550,835,905,550,550]

img = plt.imread("images/changes_of_state.png")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (8,8), num = 'Changes of State of Water')

ax.imshow(img)

annot = ax.annotate("", xy=(0,0), xytext=(30,30),textcoords="offset points",

bbox=dict(boxstyle="round", fc="w"),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->"))

annot.set_visible(False)

names = ['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation']

norm = plt.Normalize(1,4)

cmap = plt.cm.RdYlGn

sc = plt.scatter(x,y,c = 'k', marker = 's', alpha = 1, s = 250)

annot = ax.annotate("", xy=(0,0), xytext=(30,30),textcoords="offset points",

bbox=dict(boxstyle="round", fc="w"),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->"))

annot.set_visible(False)

def update_annot(ind):

pos = sc.get_offsets()[ind["ind"][0]]

annot.xy = pos

text = "{}".format(" ".join([names[n] for n in ind["ind"]]))

annot.set_text(text)

annot.get_bbox_patch().set_alpha(1)

def hover(event):

vis = annot.get_visible()

if event.inaxes == ax:

cont, ind = sc.contains(event)

if cont:

update_annot(ind)

annot.set_visible(True)

fig.canvas.draw_idle()

else:

if vis:

annot.set_visible(False)

fig.canvas.draw_idle()

fig.canvas.mpl_connect("motion_notify_event", hover)

fig.patch.set_visible(False)

ax.axis('off')

plt.show()

memgame = widgets.Button(description= "Play Memory Game",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

reset = widgets.Button(description="Reset Game",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

display(memgame)

a1 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '1?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

a2 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '2?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

a3 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '3?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

a4 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '4?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

a5 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '5?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

a6 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Melting','Freezing','Condensation','Vaporization','Deposition','Sublimation'],

description = '6?',

value = None,

disabled=False)

Qs1to3 = widgets.HBox([a1,a2,a3])

Qs4to6 = widgets.HBox([a4,a5,a6])

button_check = widgets.Button(description="Check your answers",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

def button_onclick(b):

annot.remove()

x = [470,550,810,810,1100,1180]

y = [550,550,835,905,550,550]

ax.axis('off')

plt.scatter(x,y,c = 'k', marker = 's', alpha = 1, s = 250)

a = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

corr = 10 #small correction on number

random.shuffle(a)

for i,j,k in zip(x,y,a):

ax.annotate(str(k), xy = (i-corr,j+corr), color = 'w')

display(Latex("What is the change of state corresponding to box number..."))

display(Qs1to3)

display(Qs4to6)

display(button_check)

output0 = widgets.Output()

def check_button(x):

output0.clear_output()

if a1.value == names[a.index(1)] and a2.value == names[a.index(2)] and a3.value == names[a.index(3)] \

and a4.value == names[a.index(4)] and a5.value == names[a.index(5)] and a6.value == names[a.index(6)]:

display(Markdown("Correct!"))

display(play_again)

else:

inc = []

answers = [a1.value,a2.value,a3.value,a4.value,a5.value,a6.value]

for i in range(len(answers)):

if answers[i] != names[a.index(i+1)]:

inc.append("Incorrect")

else:

inc.append("Correct")

output0.append_display_data(Latex("Those aren't quite correct, please try again."))

output0.append_display_data(Latex("1. %s, 2. %s, 3. %s, 4. %s, 5. %s, 6. %s" %tuple(inc[:])))

display(output0)

button_check.on_click(check_button)

memgame.on_click(button_onclick)

play_again = widgets.Button(description = "Play Again",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

def joue_encore(x):

clear_output()

img = plt.imread("images/changes_of_state.png")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (8,8))

ax.imshow(img)

x = [470,550,810,810,1100,1180]

y = [550,550,835,905,550,550]

ax.axis('off')

plt.scatter(x,y,c = 'k', marker = 's', alpha = 0, s = 250 )

a = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

corr = 10 #small correction on number

random.shuffle(a)

for i,j,k in zip(x,y,a):

ax.annotate(str(k), xy = (i-corr,j+corr), color = 'w')

display(Latex("What is the change of state corresponding to box number:"))

display(Qs1to3)

display(Qs4to6)

button_check = widgets.Button(description="Check your answers",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

display(button_check)

output= widgets.Output()

def check_button(x):

output.clear_output()

if a1.value == names[a.index(1)] and a2.value == names[a.index(2)] and a3.value == names[a.index(3)] \

and a4.value == names[a.index(4)] and a5.value == names[a.index(5)] and a6.value == names[a.index(6)]:

display(Markdown("Correct!"))

display(play_again)

else:

inc = []

answers = [a1.value,a2.value,a3.value,a4.value,a5.value,a6.value]

for i in range(len(answers)):

if answers[i] != names[a.index(i+1)]:

inc.append("Incorrect")

else:

inc.append("Correct")

output.append_display_data(Latex("Those aren't quite correct, please try again."))

output.append_display_data(Latex("1. %s, 2. %s, 3. %s, 4. %s, 5. %s, 6. %s" %tuple(inc[:])))

dipslay(output)

button_check.on_click(check_button)

play_again.on_click(joue_encore)

Visualizing the changes of state¶

Below is an interactive animation on the changes of state for water. Move the slider to change the temperature of the particles in the box below. Observe where the changes of state occur and how the particles gain more kinetic energy as the temperature increases.

%%html

<div style="text-align: center">

<iframe width="500px" height="420px" src="animations/changes_of_state.html" frameborder="0"></iframe>

</div>

How is Heat Transmitted?¶

There are three main methods by which heat is transmitted: conduction, convection and radiation. Below we present the basic theory behind these methods of heat transfer and some applications of how we use them to improve our lives. Examples will be provided where we analyze how the three different methods of heat transmission occur in natural processes.

1. Conduction¶

Heat transfer via conduction occurs when two bodies, with different temperatures, are in physical contact with each other. Conduction is how a stove top heats a pan or why a hot cup feels warm on your hand. Different materials conduct heat faster or slower. The conductivity of material also depends on what state it is in. These differences are expressed by a material property known as the thermal conductivity.

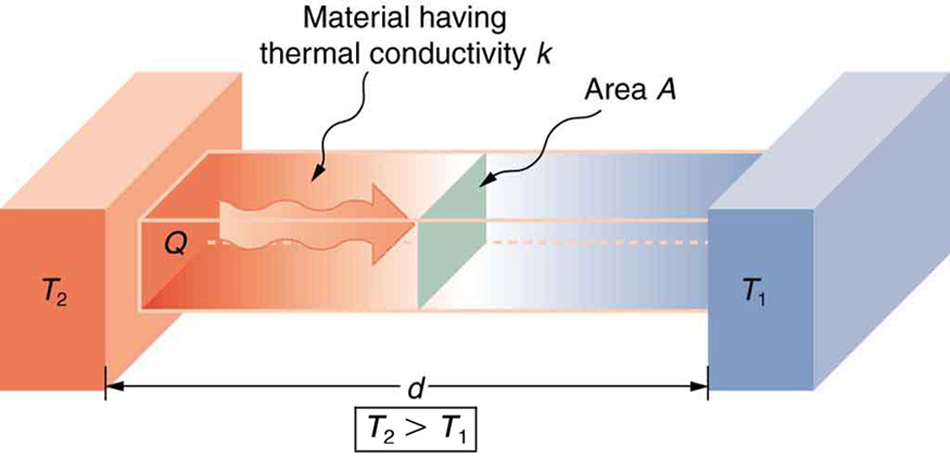

This graphic provides an visual interpretation of the heat flow, denoted as \(\rm Q\) between two bodies in contact at surface \(\rm A\) with temperatures \(\rm T_1\) and \(\rm T_2\). Let’s explore how thermal conductivity changes in different materials.

Thermal Conductivity¶

Materials with low thermal conductivity transfer heat slowly and materials with high conductivity transfer heat quickly. Can you think of some benefits of using materials with different a thermal conductivity for commercial use?

For example, consider a to-go mug. The whole purpose of this product is to keep the contained drink warm or cold. If the drink is warm, the contents will be warmer than the mug itself. They will then exchange heat to the body of the mug via conduction. If the drink is cold then the mug will transfer heat to the contents. In each case the mug is in contact with the external environment; the air outside or your hand. The environment itself, depending on its temperature, will either transfer heat to or gain heat from the mug. Since this additional heat transfer is on going, eventually the mug and the drink inside will reach the same temperature as the outside environment.

In either case, one would want the mug to have a low thermal conductivity so that it does not easily exchange heat with its environment. This will preserve the temperature of its contents. Below is an interesting video from Veritasium illustrating how conduction occurs differently in different materials.

If you haven’t heard of Veritasium before, I strongly encourage you to check the YouTube channel out. He explains a lot of topics in science and there’s always something new to learn from each video.

%%html

<div style="text-align: center">

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/vqDbMEdLiCs" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

</div>

2. Convection¶

Heat transfer via convection occurs due to the movement of molecules in a fluid (gas or liquid). Convection is perhaps the most intuitive method of heat transfer. Since it involves the flow of a gas or liquid from a warmer to a colder temperature within the fluid, it is easy to visualize. Convection does not occur in solid materials because the molecules that make up a solid do not have the ability to flow; this is what makes a solid a solid. Not unlike conduction, convection occurs from the flow of heat energy due a temperature difference within a fluid. The hotter fluid flows to regions where the fluid is cooler. It is the process which governs the currents in our oceans and the movement of air in our atmosphere. Our understanding of convection has helped us forecast the weather and even explain how energy is transported within the sun!

Why does the movement occur?

If we consider the particle model of matter, the fluid moves due to changes in kinetic energy of the particles in the fluid. The hotter regions in the fluid, the ones with more heat energy, have more “excited” particles that are colliding into one another more frequently. These regions are less dense than the colder regions. In the colder regions, the particles are colliding into one another less frequently therefore they do not spread out as much. Since there are less collisions, the particles are more concentrated in the colder region. These more dense and concentrated regions in the fluid are heavier since they have more particles in them. The cold, heavier regions will sink; allowing for the hotter regions to rise. Convection is the reason why “heat rises” in a room.

Examples of convective processes

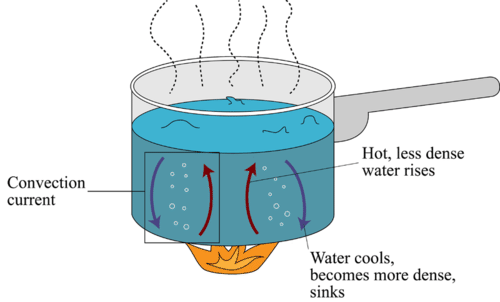

In a pot filled with water on the stove, we observe convective heat transfer in the bubbles rising to the top of the pot. These are hotter, less dense regions rising to the surface of the liquid. When these regions reach the point the that they are less dense than the surrounding air, they will evaporate and undergo a transition of state from liquid to gas.

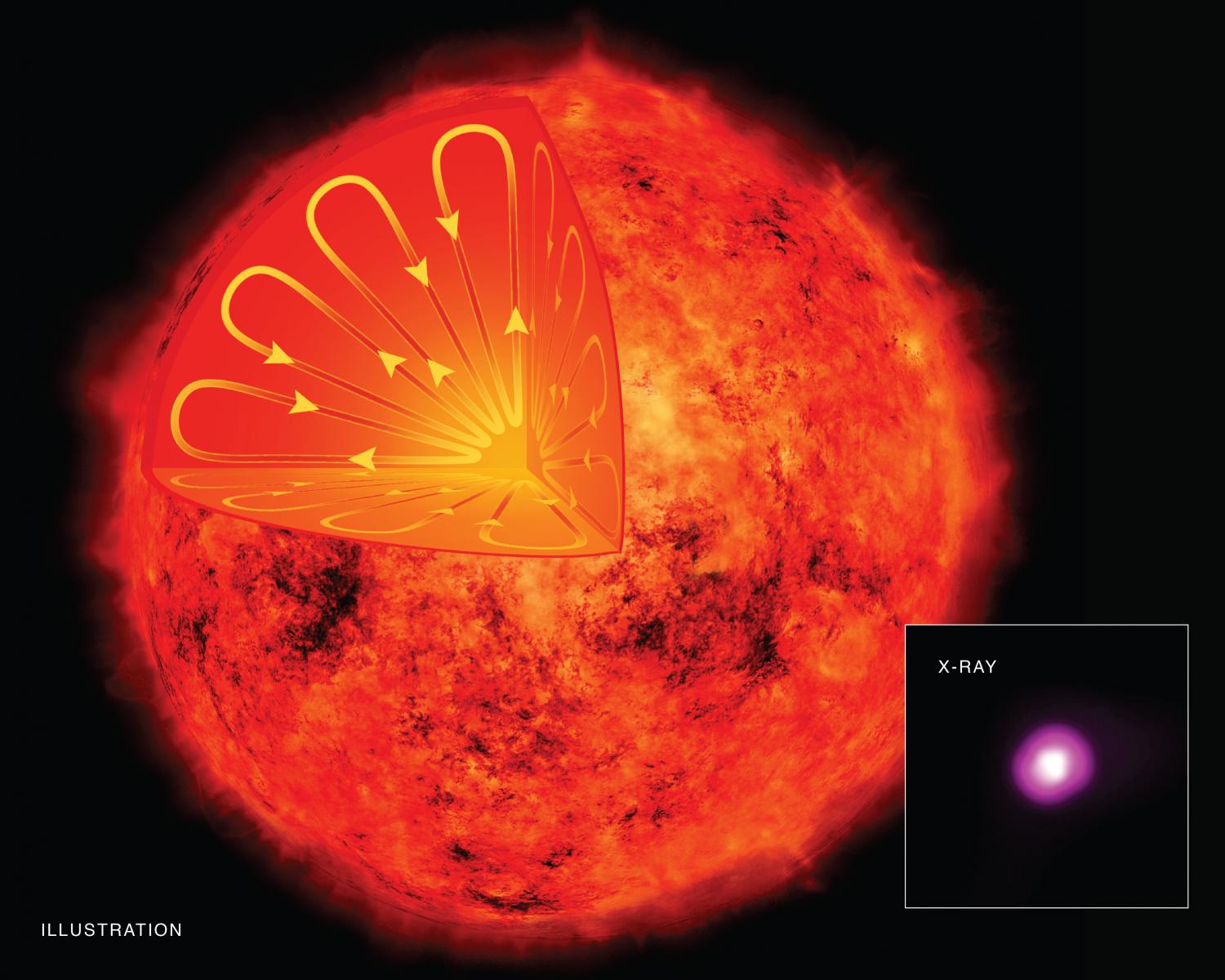

In stars, there is a zone in which energy is transported from the core of the star, where energy is produced by nuclear fusion, to the surface. This is known as the convective zone. Due to the complicated nature of energy transportation within stars, this process is difficult to model and the subject of ongoing research within the field of stellar astrophysics. Understanding convection has helped astrophysicists know more about our sun and other stars like it!

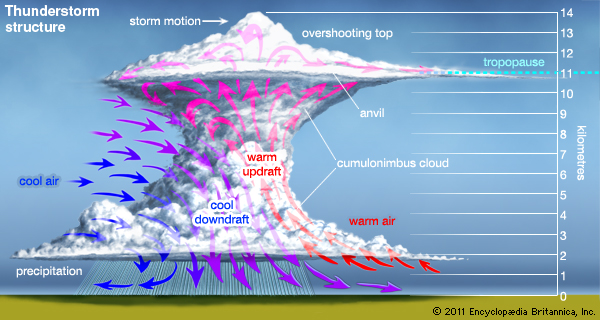

In the atmosphere, convection plays a major role in the creation of a thunderstorm. Clouds form as hotter air rises, carrying moisture with them. The air cools on its ascent, causing the moisture to condense. If the air is unstable enough, this process can occur for a longer time. This results in the formation of “cumulonimbus clouds”, which are those very tall pillowy clouds that often produce thunder and lightning. Given enough moisture, instability in the air and convection (heat transfer), a thunderstorm is likely to occur.

3. Radiation¶

Radiation is our third and final form of heat transfer to discuss. Heat transfer via radiation occurs in all matter that has a temperature above absolute 0 (0 Kelvin). It occurs from a conversion of thermal energy into electromagnetic energy. Energy is “radiated” away from a body in the form of “light”. This light varies in wavelength and is dependent on the temperature of the body; hotter objects emit radiation at shorter wavelengths that carry higher energy. For example, in a fire, you may have heard how the blue part of a fire is hotter than the red part. This is true and is due to the fact that blue light has a shorter wavelength than red light, and since the wavelength is dependent on the temperature of the material emitting it, the blue portion of a fire is hotter.

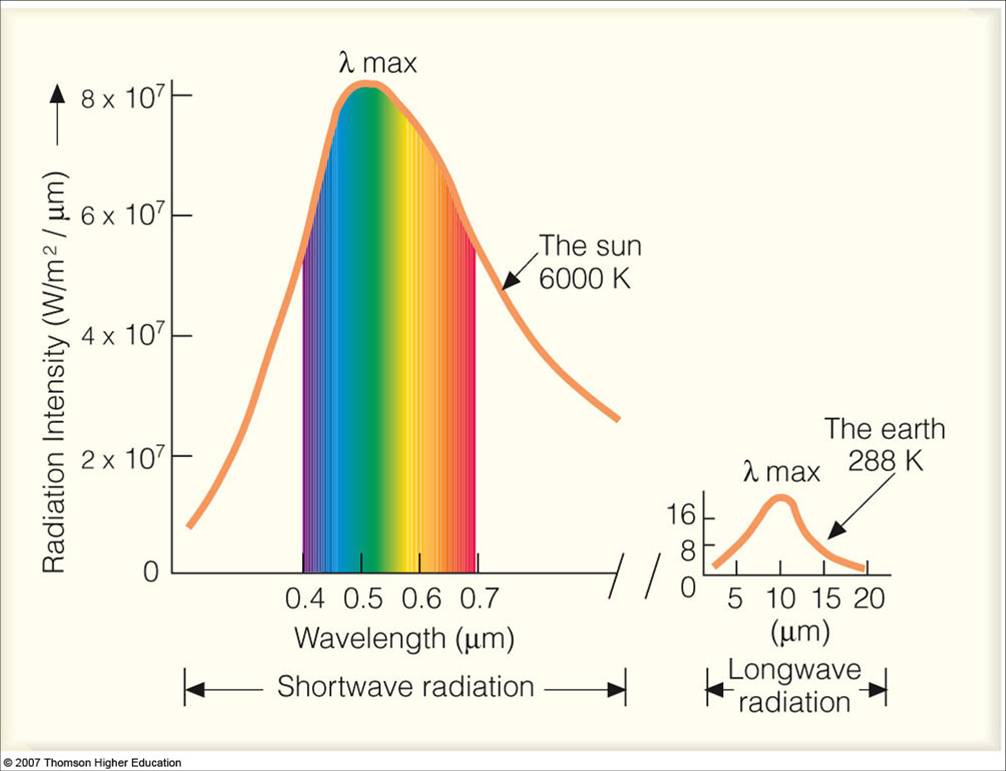

An interesting consequence of this fact comes from the analysis of the wavelengths of light radiated from the sun. Below is graphic showing the types of radiation emitted from the sun.

The most intensely radiated wavelength from the sun comes from the green part of visible light. Plants, trees, and even our eyes have become fine tuned to absorbing and perceiving more variations of the colour green because this is the most prominent radiation from the sun. Understanding thermal radiation has offered a scientific explanation for why our planet is so green.

Exercises¶

Below a list of processes in which heat transfer occurs in different forms. You will be asked to check the box for which type of heat transfer you think is correct to match the description. Press “Check Answer” to see if you were correct!

Boiling Water ¶

a1 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

disabled=False,

value = None,

continuous_update=True

)

a2 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

disabled=False,

value = None,

continuous_update=True

)

a3 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

disabled=False,

value = None,

continuous_update=True

)

a4 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

disabled=False,

value = None,

continuous_update=True

)

#create a button widget to check answers, again calling the button to display

button_check = widgets.Button(description="Check your answers",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

#compare answers to responses

def compare(l1,l2):

a = []

for i in range(0,min(len(l1),len(l2))):

if l1[i] == l2[i]:

a.append(1)

else:

a.append(0)

return a

ans1 = ['Radiation', 'Conduction', 'Convection', 'Conduction']

out = widgets.Output()

def check_button(event):

out.clear_output()

rs1 = [a1.value, a2.value, a3.value, a4.value]

if rs1 == ans1:

out.append_display_data(Markdown("Correct! Here's why : </br></br> \

1. The stove top heats up and radiates energy away from it. This is what you feels in your hand as heat. </br> \

2. The stove top conducts heat to the pot since they are in physical contact with one another. </br> \

3. Heat is transferred by fluid motion within the water via convection. </br> \

4. The gas particles carry heat energy, in the form of kinetic energy, which gets transferred via physical contact with your hand and the steam. </br> \

Since the heat transfer occurs via physical contact, the process responsible for the heat transfer is conduction. "))

else:

bien = compare(rs1,ans1)

h = []

for i in bien:

if i == 0:

h.append('Incorrect')

if i == 1:

h.append('Correct')

s = "Those aren't quite correct, please try again."

corrections = "1. %s, 2. %s, 3. %s, 4. %s" %(h[0],h[1],h[2],h[3])

out.append_display_data(Latex(s))

out.append_display_data(Latex(corrections))

button_check.on_click(check_button)

display(Markdown('1) After you turn on the stove, you hold your hand above the stove and it feels hot.'))

display(a1)

display(Markdown('2) The pot starts to heat up when placed on the stove.'))

display(a2)

display(Markdown('3) Hot water rises to the surface of the pot.'))

display(a3)

display(Markdown('4) Steam from the pot feels hot on your hand. (Somewhat tricky)'))

display(a4)

display(button_check)

display(out)

After you turn on the stove, you hold your hand above the stove and it feels hot.

The pot starts to heat up when placed on the stove.

Hot water rises to the surface of the pot.

Steam from the pot feels hot on your hand. (Somewhat tricky)

Refrigerator ¶

display(Markdown('1) Hot air is pumped out of the food compartment'))

a1 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

value = None,

disabled=False

)

display(a1)

display(Markdown('2) You grab a cold popsicle out of the refrigerator. It feels cold on your hand.'))

a2 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

value = None,

disabled=False

)

display(a2)

display(Markdown('3) How did the popsicle get cold? How did it transfer heat energy while sitting in the refrigerator?'))

a3 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

value = None,

disabled=False

)

display(a3)

display(Markdown('4) You open the refrigerator door and it feels cold inside.'))

a4 = widgets.RadioButtons(

options=['Conduction', 'Convection', 'Radiation'],

value = None,

disabled=False

)

display(a4)

#create a button widget to check answers, again calling the button to display

button_check = widgets.Button(description="Check your answers",

layout = Layout(width='30%', height='60px'),

button_style = 'info'

)

display(button_check)

#Answers to be checked against, third entry should be != Conduction, fourth is != 'Radiation'

ans = ['Convection','Conduction', 'Conduction','Radiation']

#compare answers to responses

def compare(l1,l2):

a = []

for i in range(0,min(len(l1),len(l2))):

if l1[i] == l2[i]:

a.append(1)

else:

a.append(0)

return a

outtie = widgets.Output()

def check_button(x):

outtie.clear_output()

rs = [a1.value, a2.value, a3.value, a4.value] #responses

if rs[0] == ans[0] and rs[1] == ans[1] and rs[2] != ans[2] and rs[3] != ans[3]:

outtie.append_display_data(Markdown("Correct! Here's why : </br></br> \

1. Hot air flows out of the fridge via convection. </br> \

2. Heat is transferred via convection since your hand it hotter than the popsicle. </br> \

3. Heat is transferred by radiation or conduction. The food sitting in the refrigerator radiates heat energy and also conducts heat to the colder air within the fridge. </br> \

4. Heat is transferred via conduction from your warmer self to the cold air within the refrigerator."))

else:

a = compare(rs,ans)

bien = [1,1,0,0] #This is what "a" should be

xx = compare(a,bien)

h = []

for i in xx:

if i == 0:

h.append('Incorrect')

if i == 1:

h.append('Correct')

outtie.append_display_data(Latex("Those aren't quite correct, please try again."))

outtie.append_display_data(Latex("1. %s, 2. %s, 3. %s, 4. %s" %(h[0],h[1],h[2],h[3])))

button_check.on_click(check_button)

display(outtie)

Hot air is pumped out of the food compartment

You grab a cold popsicle out of the refrigerator. It feels cold on your hand.

How did the popsicle get cold? How did it transfer heat energy while sitting in the refrigerator?

You open the refrigerator door and it feels cold inside.

Conclusion¶

In this Jupyter Notebook you learned about some aspects of the nature of thermal energy. We differentiated between heat and temperature. The particle model was used to describe the effect of heat on matter. You learned about the various modes of heat transfer:

Conduction

Convection

Radiation

You also some examples of how these processes are studied in everyday life. You also learned the different changes of state of matter. If you don’t feel like you have these memorized, I encourage you to play the memory game a few more times.

We exploit thermal energy to improve our daily lives. It is through our understanding of the processes that govern heat that we have been able to do so.

Image References

conduction : https://www.khanacademy.org/science/physics/thermodynamics/specific-heat-and-heat-transfer/a/what-is-thermal-conductivity

sun: https://phys.org/news/2016-07-astronomers-gain-insight-magnetic-field.html

thunderstorm: https://www.britannica.com/science/thunderstorm

boiling pot: https://dr282zn36sxxg.cloudfront.net/datastreams/f-d%3A5f69d56e0b81661f4564d03405f4cd0be18c94afbe66c30f9eb9a17b%2BIMAGE_THUMB_POSTCARD_TINY%2BIMAGE_THUMB_POSTCARD_TINY.

radiation diagram: http://apollo.lsc.vsc.edu/classes/met130/notes/chapter2/plank_e_sun.html