from IPython.display import display, Math, Latex, HTML, clear_output, Markdown, IFrame, YouTubeVideo

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from numpy import sqrt as sqrt

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive, interact_manual

%matplotlib inline

'''Above, we are importing all the necessary modules in order to run the notebook.

Numpy allows us to define arrays of values for our variables to plot them

matplotlib is what we use to create the figures

the display and widgets are to make the notebook look neat

'''

HTML('''<script>

function code_toggle() {

if (code_shown){

$('div.input').hide('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Show Code')

} else {

$('div.input').show('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Hide Code')

}

code_shown = !code_shown

}

$( document ).ready(function(){

code_shown=false;

$('div.input').hide()

});

</script>

<form action="javascript:code_toggle()"><input type="submit" id="toggleButton" value="Show Code"></form>''')

Newton’s Second Law¶

Newton’s three laws of motion comprise some of the most foundational thinking for the progression of physics throughout our history. They tells us qualitatively and quantitatively what happens to an object (with mass) when a force has been acted on the object. Without these laws we wouldn’t be able to send people (or Teslas) into space! In this notebook we will focus on the Newton’s Second Law after first reviewing his First Law.

Newton’s First Law¶

Latin: Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare.

English Translation: An object at rest will remain at rest unless acted upon by an external and unbalanced force . An object in motion will remain in motion unless acted upon by an external and unbalanced force.

Let’s see if we can understand better what this means and checkout a real example.

Imagine you have a ball floating in space, perfectly still, where Newton’s \(1^{\rm st}\) law tells us it will remain motionless for eternity. It will remain this way unless a force acts on the ball. In the cell below, we can see this happening! The ball sits motionless UNTIL you apply the force. Likewise, once a force is applied and the ball starts to move it will continue to do so forever unless another force opposes this motion. Try it out below!

%%html

<iframe src = 'p5_animations/Newtons_First.html' width = "920px" height = "320px" frameBorder="0"></iframe>

But how can we quantify what this force is doing when it acts on the ball? This can be described with Newton’s Second Law.

Newton’s Second Law¶

Latin: Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae, et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur.

English Translation: The rate of change of momentum of a body is equal to the resultant force acting on the body and is in the same direction.

Another way to represent this law, and the most commonly used form, is with the equation

\(\vec{F} = m\vec{a}\)

where \(\vec{F}\) is the force, \(m\) is the mass of the body which experiences the force and \(\vec{a}\) is the acceleration of that same body. This allows us to carefully analyze the motion of an object once it has been impacted by the force. An important aspect of understanding this motion is to be familiar with vectors and their notation, so before we get more in depth with Newton’s \(2^{\rm nd}\) Law let’s look at what vectors are!

Vectors and Their Notation¶

The standard definition for a vector says that they represent both the magnitude and direction of some physical quantity. These quantities can include forces, velocity, acceleration and electromagnetic fields, just to name a few. Vectors (we will use an arbitrary variable \(v\)) are often denoted as \(\vec{v}\) or as \(\boldsymbol{v}\). Both styles are valid choices when typing on a computer but of course by hand it is most acceptable to write vectors with the arrow notation.

So now, what does a vector actually look like? Well when looking at the cartesian coordinate system (Euclidean space) we get the usual coordinate axis that looks something like this.

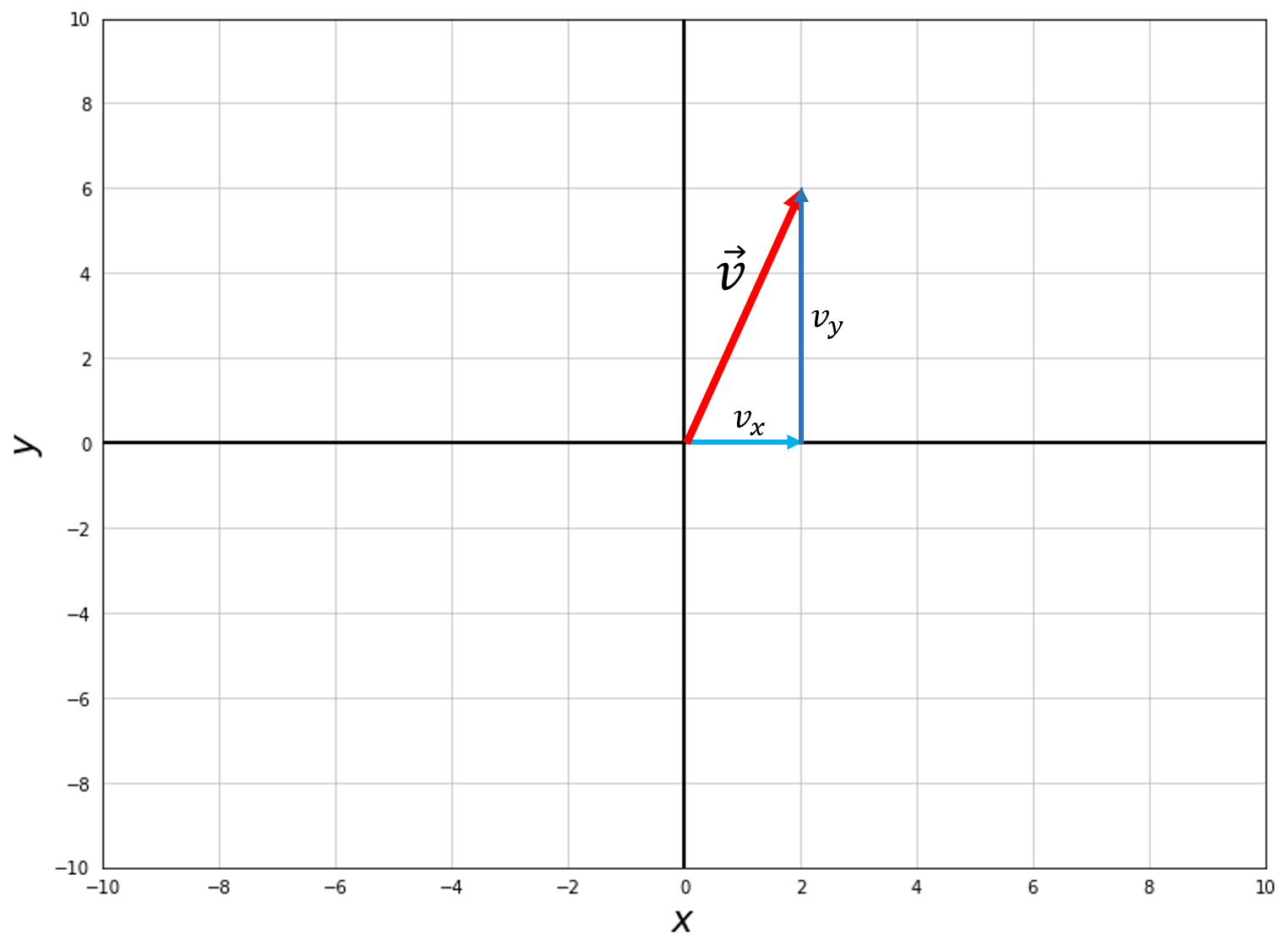

Within these coordinates it is then very easy to generate a vector that has both magnitude and direction. Check it out!

To obtain the magnitude of this vector it only takes simple trigonometry (only in cartesian coordinates for 2D space). We define the magnitude as

\(\lvert\lvert\vec{v}\rvert\rvert = \sqrt{v_x^2 + v_y^2}\)

where \(v_x\) and \(v_y\) are the \(x\) and \(y\) components of a vector respectively. As you may have been able to tell, the magnitude of a vector is just found using the Pythagorean theorem. There can be many ways to write the components of a vector but in this notebook we will use the notation \(\vec{v} = (v_x,v_y)\) for vectors that begin at the origin. For the red vector shown above we get that

\(\vec{v} = (2,6)\)

and the magnitude is

\(\lvert\lvert\vec{v}\rvert\rvert = \sqrt{2^2 + 6^2} = \sqrt{40} \approx 6.3\)

Next it is important to understand how to interpret the direction of a vector. This is of course, merely the direction that the arrow points in our diagram but it should be known that this direction comes from the \(x\) and \(y\) components that make up the vector. In this case this is \((v_x,v_y)\) where \(v_x\) is in the \(x\) direction and \(v_y\) is in the \(y\) direction so the net force is pointed in both the \(x\) and \(y\) directions.

Back to Newton’s Second Law¶

So now that we are familiar with vectors let’s look at how Newton’s Second law impacts the motion of objects. Again, Newton’s Second Law is written as

\(\vec{F} = m\vec{a}\)

where now we know that the net force \(\vec{F}\) and the acceleration \(\vec{a}\) are vectors. So of course this tells us that the acceleration is in the same direction as the net force. To get the full picture of how this law can describe the motion of an object we’ll look at the components of the law in 2 separate parts, starting with net force, then onto acceleration and mass.

Net Force¶

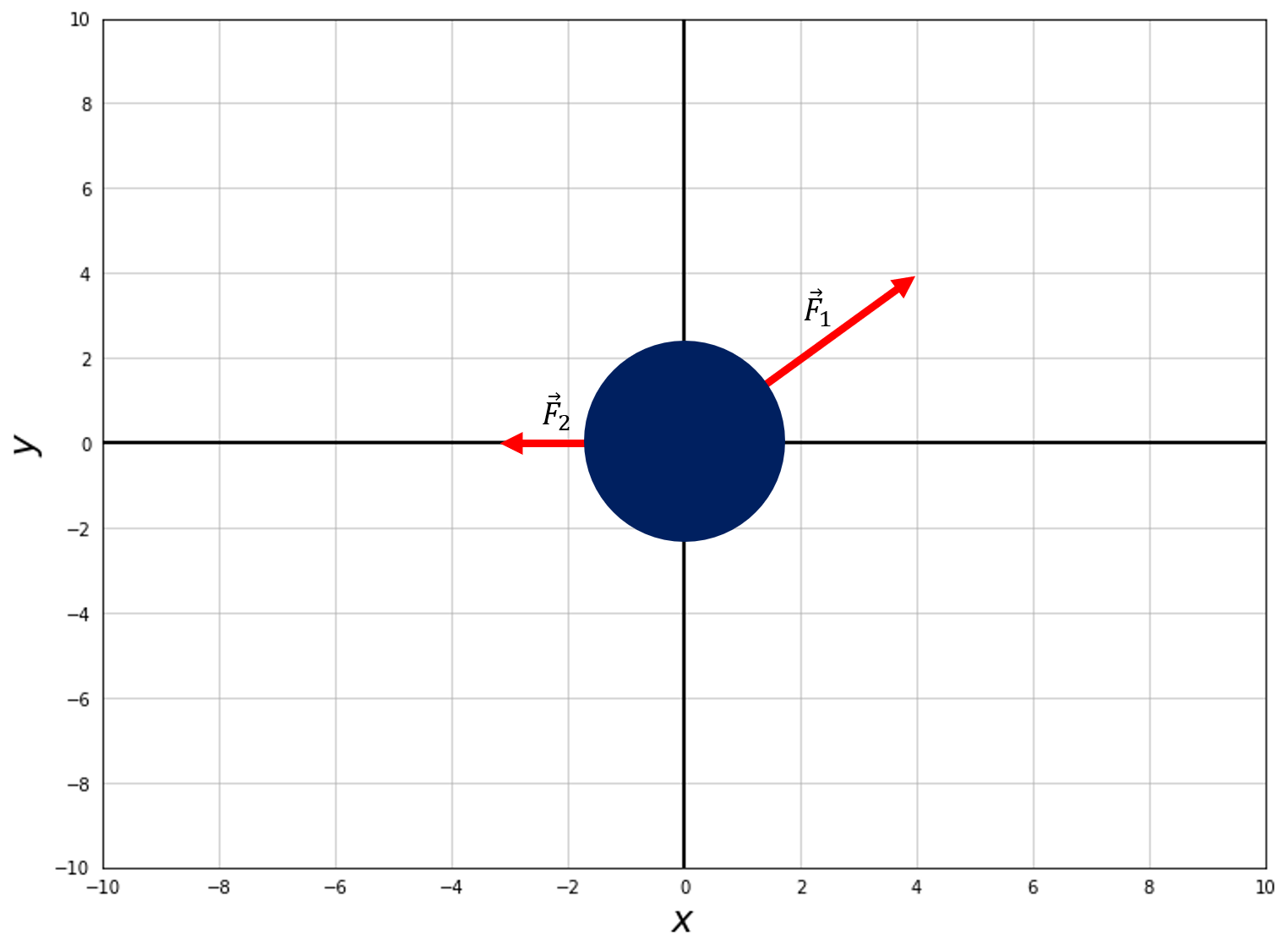

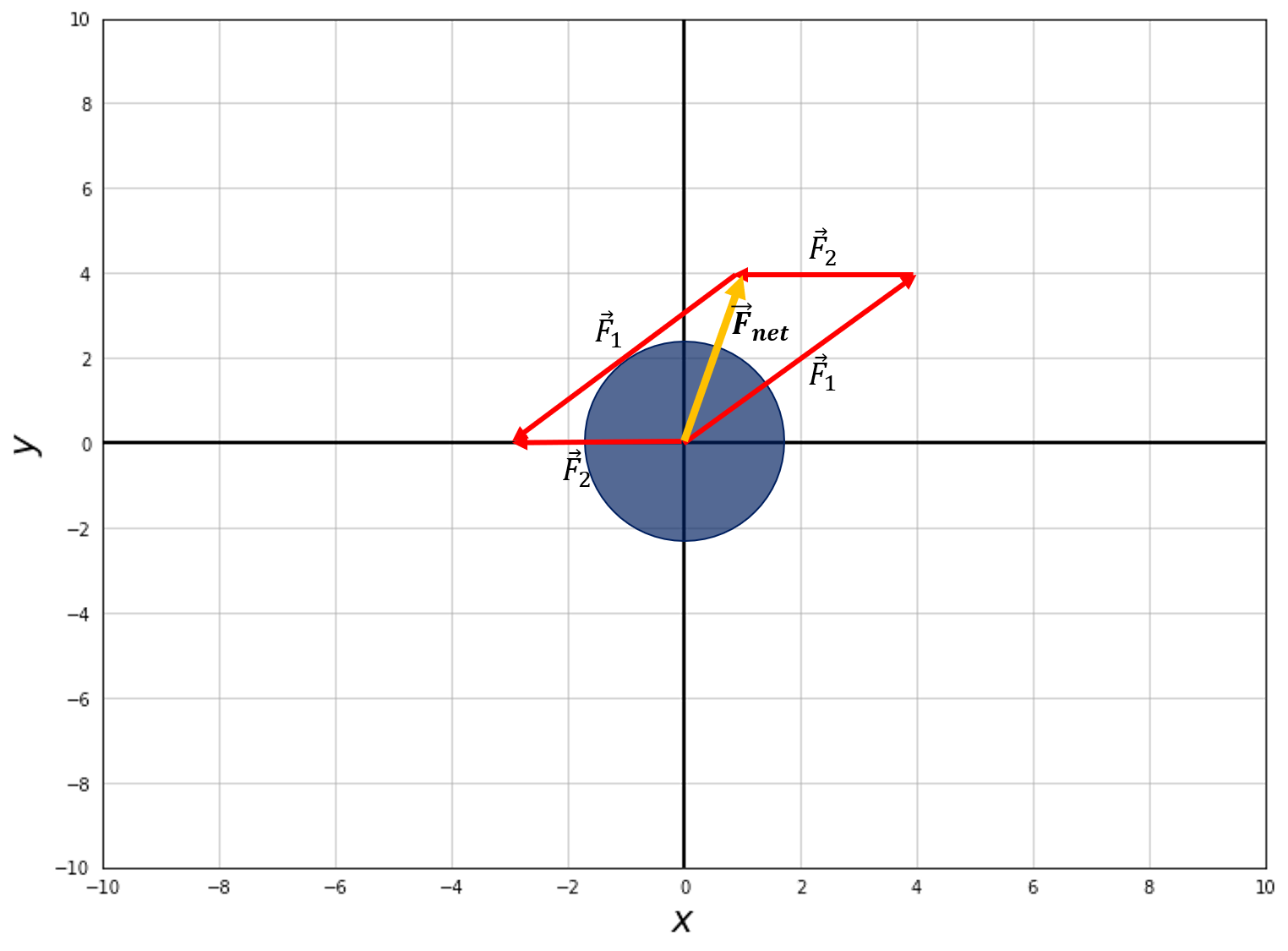

A force is merely defined in Physics as something that changes the motion of an object. You’ll often hear it defined as a “push” or a “pull”, which works in the context of 2D problems but doesn’t give as clear of a description in 3D so this notebook will refrain from using that nomenclature. There are many types of forces that we experience and interact with every day. Some of these include applied forces, electric and magnetic forces, gravity, friction, etc. If there are 2 or more of these forces acting on a body, we get a net force in the resulting direction. To understand how a net force is quantified here is an image showing the resultant, net force from two individual forces.

display(HTML("<table><tr><td><img src='images/Vector_3.png'></td><td><img src='images/Vector_4.png'></td></tr></table>"))

|  |

The net force is merely calculated using vector addition principles, which we will not cover here, but should help to intuitively visualize a net force.

Acceleration and Mass¶

As we saw in the single body example of the ball experiencing the force of gravity and an applied force (of wind), the net force caused a change in the motion of the ball. If you haven’t guessed it yet, this is because the acceleration is directly proportional to the net force acting on an object with mass. Newton’s Second Law tells us exactly this! If we were to manipulate the law so that we are solving for acceleration instead of the force we get

\(\vec{a} = \frac{\large \vec{F}}{\large m}\)

where now we can see that the acceleration depends linearly on the net force and inversely with mass. BUT BE CAREFUL! This does not necessarily mean that if we apply the same force to objects of differing mass that the heavier objects will accelerate slower than the lighter ones. It depends on what type of force is acting on the objects. For example let’s simplify our original case and only induce a force of gravity on several objects of varying mass (where no air resistance is present, i.e. space).

%%html

<iframe src = 'p5_animations/Gravity.html' width = "920px" height = "420px" frameBorder="0"></iframe>

They all fell at the exact same rate! This is because the force of gravity is known to be

\(\vec{F}_g = -m\vec{g}\)

so when substituted into Newton’s Second law we get that

\(\vec{a} = -\vec{g}\)

which shows us that no matter what the mass of the objects are, they all accelerate downwards at a rate of \(\vec{g}\). Now let’s consider a material that induces a drag force on these falling objects. In general the drag force is defined as

\(\vec{F}_d = -\frac{1}{2}\rho \vec{v}^2 C_D A\)

where \(\rho\) is the density of the material, \(\vec{v}\) is the velocity of our objects, \(C_D\) is the drag coefficient (similar to a friction coefficient) and \(A\) is the surface area in contact with the drag material. For the purpose of this exercise we will simplify the force to

\(\vec{F}_d = -c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\)

where \(c_0\) is just a constant value. The two important aspects of this equation is now the direction in which the force points and the value of \(C_D\), which determines how strong the force is.

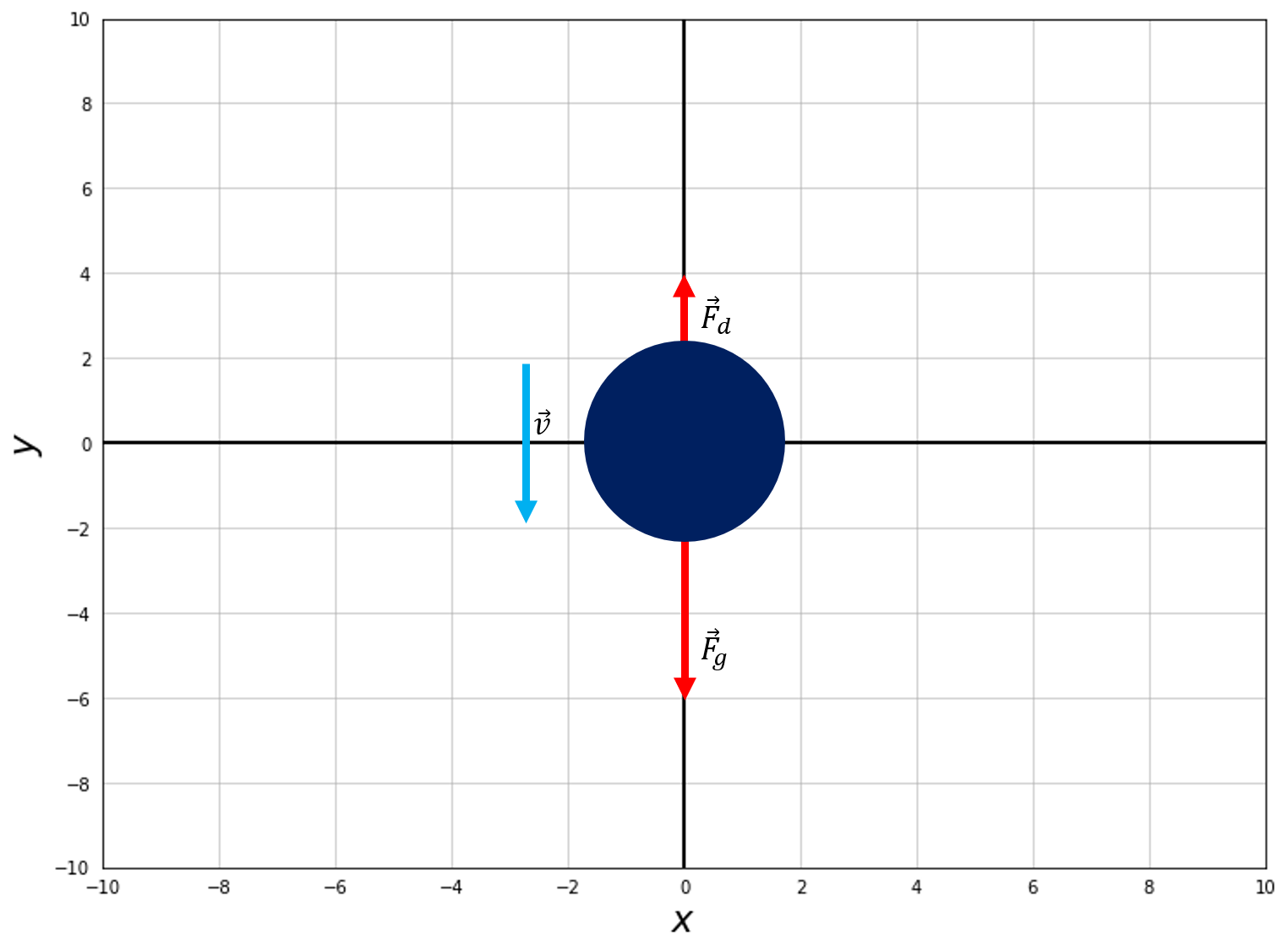

The negative sign here indicates that this force acts in the opposite direction to the velocity of an object. So in a scenario where an object is experiencing both a gravitational and drag force, what will happen to the acceleration? and what will the dependence on mass be? Well first, to find the net force, let’s look at a force body diagram and then add the forces together.

Notice here that the drag force points opposite the direction of the velocity! With this depiction we can go on to write the net force and acceleration as

\(\vec{F}_{net} = -m\vec{g} + c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\)

\(\vec{a} = \frac{1}{m}(-m\vec{g} + c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D) = -\vec{g} + \frac{1}{m}c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\)

From this there is one important question we could ask ourselves; what are the conditions for the acceleration to be positive or negative? The inflection point between these scenarios would be where there is no acceleration so let’s start there. If we had a scenario where the acceleration was 0 we would find that

\(\vec{g} = \frac{1}{m}c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\)

or in other words, the forces are balanced. Now if they are unbalanced this must result in an acceleration. Which direction the object accelerates depends on the condition of whether or not our drag force is greater than or less than the gravitational force.

Below is a simulation where several balls begin in free fall as a result of gravity acting on them, where they go on to hit a substance (we’ll assume it’s water) which will apply a drag force. Before running the simulation ask yourself, will the balls fall at the same rate once they hit the water? Will the heavier balls fall quicker or will the smaller ones? Look again at our final equation for acceleration

\(\vec{a} = -\vec{g} + \frac{1}{m}c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\)

Now check out what happens!

%%html

<iframe src = 'p5_animations/Drag.html' width = "900px" height = "620px" frameBorder="0"></iframe>

The smaller balls fall at a slower rate than the larger ones do once they hit the material. This is because our drag term in the acceleration, \(\frac{1}{m}c_0\vec{v}^2 C_D\), has an inverse dependence on the mass of the ball. Therefore, if you were to decrease the mass of the ball, the drag force will increase the acceleration in a positive, upwards direction, counteracting the effect of the gravitational effect. Thus, the heavier balls will experience “more” of the gravitational force and fall downwards at a faster rate.

Beyond \(\boldsymbol{\small F=ma}\)¶

One of the forces we have touched on quite a bit is that of the gravitional force \(F_g = mg\). It was stated earlier that \(g\) was defined to be \(9.81\) \(\rm m/s^2\), but this is only the case for when we are situated on the surface of the Earth. Our Earth itself experiences a gravitational force, influenced by our Sun, and this is what causes ours and all the other planets to orbit around it. So this gravitational acceleration term (\(g\)) must have a more generalized form right? Indeed it does, we know that in general, the gravitational acceleration is

\(g = \frac{\large GM}{\large r^2}\)

where \(M\) is the mass of the gravitational influencer (VERY massive object), \(G\) is the universal gravitational constant and \(r\) is the distance between the influencer and the effected body with a mass \(m\). The direction of this force is in the radial direction, meaning that it always points from the center of one object to the center of the other object. From this we get a general form for the gravitational force

\(F_g = \frac{\large GMm}{\large r^2}\)

It is important to realize that the direction of this force is along the distance or separation vector \(\vec{r}\) and is negatively oriented. In the environment of standing on Earth this should be intuitive as we are constantly being pushed downwards, back to the surface when we try to jump in the air or send rockets into space. How might this work for an orbiting planet ? And why doesn’t a planet just fall into the Sun, just like how we are brought back to the ground ? A crucial factor for the stability and effectively eternal nature of the planet’s orbits has to do with the orbital velocity they obtained during the Solar System’s creation.

During the formation of a star, there may exist a Protoplanetary disk that violently orbits around the young star. If conditions are satisfactory for planetary formation, the material in the disk will start to clump and create it’s own gravitational field, which in turn attracts more material, forming gaseous or rock based planets, depending on their distance from the star. Due to conservation of angular momentum and energy, the orbital velocity that this material had while the star was forming, remains long after the star and planets have formed. Thus, as we see in our own Solar System, this is how the planets perpetually orbit around the Sun.

YouTubeVideo("f9rBJDajwPc", width=560, height=315)

Now back to the gravitational force and its role in all of this. Without the constant gravitational acceleration inwards, the planets would merely fling off their elliptical orbits and off into interstellar space. Let’s see what this looks like with some vectors indicating how all these effects are working together.

%%html

<iframe src = 'p5_animations/Orbit.html' width = "620px" height = "550px" frameBorder="0"></iframe>

Questions¶

Q1. By looking at the force body diagram shown below, click on the vector (arrow) at the bottom of the screen that you think represents the net force vector.

%%html

<iframe src = 'p5_animations/Vector_Q1.html' width = "480px" height = "430px" frameBorder="0"></iframe>

Q2. If a force \(F = \frac{\large kq_1q_2}{\large r^2}\) is applied to 2 objects, one with mass \(m_1\) and the other with mass \(m_2\), where \(m_2 > m_1\), which object will accelerate faster? Object 1 with mass \(m_1\) or object 2 with mass \(m_2\) ? To start off, try equating \(F=ma\) to \(F=\frac{\large kq_1q_2}{\large r^2}\) and then solve for the acceleration and see how it behaves with respect to the mass.

Click on Run Interact to check your answer.

s = {'description_width': 'initial'}

# Run Interact Button parameters

@interact_manual(answer=widgets.Textarea(

value=' ',

placeholder='Type something',

description='Type in m1 or m2 for your selection',

disabled=False,

style=s

))

# Get correct answer

def get_a(answer):

answer = answer.lower()

if "m1" in answer or "object 1" in answer:

display(Markdown("Correct! The lighter mass, $m_1$, would accelerate faster in this scenario."))

elif "m2" in answer or "object 2" in answer:

display(Latex("Close! It's actually $m_1$ that would accelerate faster. Since our mass variable is in the denominator of the equation, as we increase the mass, the acceleration decreases."))

else:

display(Markdown("Please enter `m1` or `m2`"))

Conclusion¶

Great, you’ve reached the end of your journey through Newton’s Second Law! It’s important to remember the major aspects of what we covered throughout this notebook. Newton’s Second Law is crucial in explaining how an object behaves once a force has been applied. We know that it’s acceleration is directly proportional to the force itself. As well it should be clear that the acceleration is ALWAYS in the same direction as the net force on the object. How the mass of the object effects the acceleration is completely dependent on the analytical form of the force as we saw throughout through examples such as the falling balls hitting the water. Hopefully you’re now more comfortable with all these ideas and they can be translated into understanding more about physics !