%%html

<script>

function code_toggle() {

if (code_shown){

$('div.input').hide('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Show Code')

} else {

$('div.input').show('500');

$('#toggleButton').val('Hide Code')

}

code_shown = !code_shown

}

$( document ).ready(function(){

code_shown=false;

$('div.input').hide()

});

</script>

<p> Code is hidden for ease of viewing. Click the Show/Hide button to see. </>

<form action="javascript:code_toggle()"><input type="submit" id="toggleButton" value="Show Code"></form>

Code is hidden for ease of viewing. Click the Show/Hide button to see.

#!pip install --upgrade --force-reinstall --user git+git://github.com/callysto/nbplus.git#egg=geogebra\&subdirectory=geogebra

try:

from geogebra.ggb import *

except ImportError:

!pip install --upgrade --force-reinstall --user git+git://github.com/callysto/nbplus.git#egg=geogebra\&subdirectory=geogebra

from importlib import reload

import site

reload(site)

from geogebra.ggb import *

ggb = GGB()

from __future__ import print_function

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive, fixed, interact_manual

import ipywidgets as widgets

import IPython

from IPython.display import HTML,display, Math, Latex, clear_output

import math

import random

import numpy as np

import plotly.offline as py

from plotly.offline import init_notebook_mode, iplot

import plotly.graph_objs as go

Binary decimal conversion¶

Introduction¶

A positional numeral system is a way of writing numbers using place value.

Our usual way of writing numbers is an example:

In a number like 1234, the 4 is in the ‘ones’ spot, the 3 in the ‘tens’ spot, and so on.

Each position represents a power of 10, so we call this the decimal, or base-10 system.

This notebook will look at positional numeral systems in general, but a focus on two familiar examples:

The decimal (base-10) system we all know and love, and the binary (base-2) system.

Topics include:

the base of the numeral system

how the choice of base effects the digits we use to write a number

how to convert between decimal and binary representations of a number.

Big Ideas¶

Here are some key takeaways you should have in mind as you progress through this notebook:

Computers understand numbers in binary, while humans understand decimal.

Conversion from decimal to binary is fundamental to human-computer interaction.

Understanding this process requires only basic arithmetic: addition, subtraction, and powers.

Background information¶

Numeral systems¶

In mathematical terminology, a number system refers to the type of number being used.

Number systems include the integers, the rational numbers (fractions), and real numbers.

A numeral system refers to the way we write those numbers down.

The numeral system we use when we write a number like 3127 is called the decimal system.

You’ve gotten so used to using the decimal system that you understand the number 3127 without thinking!

Take a moment to remind yourself that the position of each digit represents a value: 1, 10, 100, etc.

The digit in that position then tells us how many of that quantity we have.

In 3127, there are 3 thousands, one hundred, two tens, and seven ones.

But our method of expressing numbers is by no means universal.

Another numeral system you’ve probably encountered is that of Roman numerals.

The Roman system uses symbols instead of position to represent certain quantities.

We count how many times each symbol appears to know how many of that quantity we have.

For example, the Roman numeral system uses I for 1, V for 5, X for 10, C for 100, and D for 1000, among others.

In the Roman system, the number 3127 is written as MMMCXXVII:

Note that in the Roman system, there is no symbol for zero: a number like 210 has no ones, so we don’t write any.

The number 210 is written CCX. Many early numeral systems did not have a zero.

The invention (discovery?) of zero is usually credited to India, around the 4th or 5th century.

However, zero was also used in Mayan calendars.

The number zero is an interesting topic in its own right, but it’s not the subject of this notebook.

If you’re curious, you might enjoy this Scientific American article.

Binary and decimal numbers are two examples of positional numeral systems, where the relative placement of digits tells us about the values they represent.

One of the earliest examples of a positional system is the remarkable Babylonian sexagesimal (base-60) system.

Our numeral system traces its origins back to India and the Middle East, and is known as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.

This is a decimal system, where positions represent powers of 10, and symbols represent numbers from 0 to 9.

For example, as we mentioned above, the expression 3127 is convenient shorthand for

Notice that 1000, 100, 10, and 1 are all powers of 10: \(1=10^0, 10=10^1, 100=10^2\), and \(1000=10^3\).

When each position represents successive powers of some number, we call that number the base of the system.

The decimal system uses base 10. The binary system, which is essential to computing, uses base 2.

Why Binary?¶

Why do computers use binary? First, we might ask: why do we use decimal?

We’ve been using decimal so long, you may not have wondered why we chose the base-10 number system for our everyday number needs.

(There’s a pretty good chance that it has something to do with humans having 10 fingers.)

Regardless of what led to it, tricks we’ve learned along the way have solidified base-10’s place in our heart.

Everyone can count by 10s. We even round large numbers to the nearest multiple of 10. We’re obsessed with 10!

Computers, being electronic machines, only understand two things:

‘ON’ or ‘1’: electricity is flowing (through circuit, gate, transistor, whatever).

‘OFF’ or ‘0’: electricity is not flowing.

In a computer, everything must be represented as collections of ONs and OFFs.

Unfortunately, this scheme is difficult for humans to process.

To make things easier on ourselves, humans represent “computerian” as binary numbers:

ON is represented by a 1, and OFF is represented by a 0.

So instead of “OFF ON ON OFF”, we humans can read or write this as “0110”.

|

Base and Digits in a Positional System¶

The base in a positional numeral system like Hindu-Arabic is the number whose powers we represent by the position of the digits in a number.

Note that the value of the base is also the number of different symbols we need for digits.

For example, the decimal (base-10) system uses 10 digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

In some computer applications (like many WiFi passwords) a hexadecimal (base-16) system is used, with digits

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, a, b, c, d, e, f.

Of course, we also use “base” to refer to the number that gets multiplied when applying an exponent.

Examples:

In \(8^{2}\), 8 is the base, and the result is \(8 × 8 = 64\).

In \(5^{3}\), 5 is the base, and the result is \(5 × 5 × 5 = 125\).

This isn’t really a coincidence, since we use powers of the base to reconstruct numbers from positional notation.

The way our notation works is as follows:

Position of a digit (read from right to left) tells us which power of the base to use.

The digit in that position tells us what to multiply that power by.

Any integer greater than 1 can be used as a base. (Why can’t we use 1?)

For a hypothetical “base-\(r\)” system, we would have \(r\) symbols to represent the digits, and each position represents a power of \(r\).

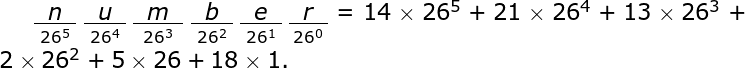

For example, we could imagine a base-26 system with each letter of the alphabet representing a digit.

(It’s doubtful anyone would want to use this system, but we can imagine it!)

In this system, the word “number” would actually be a number!

If we assign each letter its place value in the alphabet, we have

$\(

n = 14, u = 21, m = 13, b = 2, e = 5, r = 18,

\)$

and

This doesn’t seem very practical, however, so let’s sum up the key points and move on to numbers in decimal and binary.

The base of a positional numeral system is equal to the number of digits (symbols) needed to represent numbers in that system.

The position of a digit tells us what the corresponding power of the base should be.

We multiply that power by the value of the digit, for each digit present.

Finally, we add everything up to get our number.

For a number \(a_na_{n-1}\cdots a_2a_1a_0\) with digits \(a_0, a_1, \ldots, a_n\) written in base \(r\), we get the number

We won’t do it here, but see if you can convince yourself any number can be written uniquely in any base. We never miss a number, and we never have two different ways of writing down the same number.

While working with numbers of different bases, its best to put the base as a subscript to the number to avoid confusion like \((Number)_{Base}\). For example in order to represent a binary number we place 2 as a subscript like \((11)_{2}\) and 10 to denote decimal numbers like \((11)_{10}\).

An answer to an impractical problem.¶

In the example above, were you left wondering what (base-10) number is “number” in (base-26)?

We can ask the computer to calculate it for us:

14*26**5 + 21*26**4 + 13*26**3 + 2*26**2 + 5*26 + 18

176165748

Counting in binary¶

We can count in decimal endlessly, even in our sleep, but how can we count in binary?

Zero and one in base-two should look pretty familiar: 0 and 1. From there things get decidedly binary.

In decimal, we start in the ‘ones’ position, and count until we run out of digits:

$\(0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.\)\(

After 9, we hit the next power of 10, so we add 1 to the 'tens' position, and reset the'ones' to 0.<br>

Then we go back to counting in the 'ones' position until we reach 9 again:

\)\(10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19.\)$

Now, we increase the ‘tens’ digit by 1 again, and reset the ‘ones’, getting 20.

We continue like this until we reach 99, and then we’re ready to add a 1 in the ‘hundreds’ position.

When we do, the digits in both the ‘tens’ and ‘ones’ positions reset to zero, and then we continue the process.

Counting in binary is similar, with two important differences:

Positions represent powers of 2, not 10: \( 2^0=1, 2^1 = 2, 2^2 = 4, 2^3 = 8, 2^4 = 16, 2^5 = 32, 2^6=64\), etc.

Digits are only 0 and 1, so the ‘change position and reset to zero’ step is a lot more frequent!

Remember that we’ve only got those two digits, so as we do in decimal, when we run out of symbols we shift one column to the left, add a 1, and turn all of the digits to the right of that column to 0.

So after 1 we get 10, then 11, then 100. Let’s start counting…

Decimal |

Binary |

|---|---|

0 |

0000 |

1 |

0001 |

2 |

0010 |

3 |

0011 |

4 |

0100 |

5 |

0101 |

6 |

0110 |

7 |

0111 |

8 |

1000 |

9 |

1001 |

10 |

1010 |

11 |

1011 |

12 |

1100 |

13 |

1101 |

14 |

1110 |

15 |

1111 |

Converting between decimal and binary notation.¶

Converting binary to decimal¶

Mathematically, this is straightforward. The digits in binary are called bits.

Each position represents a power of 2. We multiply each power of 2 by the bit in that position, and then add it all up.

Example:¶

To convert the number 1101 from binary to decimal, we compute as follows: \(\begin{aligned} 1101 &= 1 * 2^{3} + 1 * 2^{2} + 0 * 2^{1} + 1 * 2^{0} \\ &= 1*8+1*4+0*2+1*1\\ &= 8+4+1\\&=13 \end{aligned}\)

Interactive Method¶

We will now demonstrate an interactive approach to doing this conversion.

Our implementation uses buttons on a computer screen, but you can do this “in real life” as well!

For demonstration we start off with a 5 bit number; that is, a 5 digit binary number, which can represent up to 31 in decimal.

Represent each binary digit with a single card, so there will be 5 cards.

Mark one side of each card with a power of 2: our five cards will be 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16.

Mark the other side with a 0.Arrange the cards to reflect our positional system: Our order is 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

The side with the power of 2 represents 1 in binary and the other side represents 0.

Start with the 0 on each card. Choose a binary number, then flip the cards whose digit is 1.

For example, if we chose the number 11001, we flip the 16, the 8, and the 1.Now to convert to decimal we just add up the numbers showing in the cards!

For 11001 we have \(16+8+0+0+1=25\), so 11001 in binary is equivalent to 25 in decimal.

Applet Instructions:¶

Create a number in binary: clicking on a button with a 0 turns it into a 1.

The corresponding power of 2 below will change colour, and the 0 in front will change to a 1.

The decimal equivalent will appear at the bottom.

%%HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<style>

.button {

padding: 15px 25px;

font-size: 24px;

text-align: center;

cursor: pointer;

outline: none;

color: #fff;

background-color: #4CAF50;

border: none;

border-radius: 15px;

box-shadow: 0 9px #999;

}

.button:hover {background-color: #3e8e41}

.disabled {

opacity: 0.6;

cursor: not-allowed;

}

.button:active {

background-color: #3e8e41;

box-shadow: 0 5px #666;

transform: translateY(4px);

}

.txtbox{

display: block;

float: left;

height: 50px;

width: 50px;

font-size: 24px;

}

.new-meows{

padding: 10px;

border: 1px solid grey;

margin : 10px;

width: 97%;

display:flex;

}

.divider{

width:10px;

height:auto;

display:inline-block;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h3>Enter a binary number</h3><br>

<button id="card1" onclick="myFunction(this.id);myFunction1(this.id, 'Decimal_card_16', 'box1');" class= "button">0</button>

<button id="card2" onclick="myFunction(this.id);myFunction1(this.id,'Decimal_card_8', 'box2' );" class= "button">0</button>

<button id="card3" onclick="myFunction(this.id);myFunction1(this.id,'Decimal_card_4', 'box3');" class= "button">0</button>

<button id="card4" onclick="myFunction(this.id);myFunction1(this.id,'Decimal_card_2', 'box4');" class= "button">0</button>

<button id="card5" onclick="myFunction(this.id);myFunction1(this.id,'Decimal_card_1', 'box5');" class= "button">0</button>

<br>

<br>

<h3>Decimal Equivalent of the given binary number</h3>

<div class = "new-meows">

<input type="text" id = "box1" value="0" class ="txtbox" /> <font size="24" style= vertical-align: middle;> × </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<button id="Decimal_card_16" class= "button ">16</button><font size="24"> + </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<input type="text" id = "box2" value="0" class ="txtbox" /> <font size="24"> × </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<button id="Decimal_card_8" class= "button ">8</button> <font size="24">+</font>

<div class="divider"/>

<input type="text" id = "box3" value="0" class ="txtbox" /> <font size="24"> × </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<button id="Decimal_card_4" class= "button ">4</button><font size="24">+</font>

<div class="divider"/>

<input type="text" id = "box4" value="0" class ="txtbox" /> <font size="24"> × </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<button id="Decimal_card_2" class= "button ">2</button><font size="24">+</font>

<div class="divider"/>

<input type="text" id = "box5" value="0" class ="txtbox" /> <font size="24"> × </font>

<div class="divider"/>

<button id="Decimal_card_1" class= "button ">1</button><font size="24"> =</font>

<div class="divider"/>

<input type="text" id = "box6" value="" class ="txtbox" />

</div>

<script>

function myFunction(clicked_id) {

var Button_id = document.getElementById(clicked_id);

if (Button_id.innerHTML === "0") {

Button_id.innerHTML = "1";

} else {

Button_id.innerHTML = "0";

}

}

</script>

<script>

function setColor(btn, color_id) {

var Button_id = document.getElementById(btn);

if (color_id == 1) {

Button_id.style.backgroundColor = "#FF0000"

}

else {

Button_id.style.backgroundColor = "#4CAF50"

color_id = 0;

}

}

</script>

<script>

function setValue(box_id, txt_id) {

document.getElementById(box_id).value = "1";

if (txt_id == 1) {

document.getElementById(box_id).value = "1";

}

else {

document.getElementById(box_id).value = "0";

}

}

</script>

<script>

var value1, value2, value3, value4, value5;

var result = 0;

function myFunction1(clicked_id, decimal_card, txt_box_no) {

//value1 = 0;

//value2 = 0;

//value3 = 0;

//value4 = 0;

//value5 = 0;

var Button_id = document.getElementById(clicked_id);

if(clicked_id ==="card1" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="1"){

value1 = 16;

result = result + value1;

setColor(decimal_card, 1);

setValue(txt_box_no, 1);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card1" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="0"){

result = result - 16;

value1 = 0;

setColor(decimal_card, 0);

setValue(txt_box_no, 0);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card2" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="1"){

value2 = 8;

result = result + value2;

setColor(decimal_card, 1);

setValue(txt_box_no, 1);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card2" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="0"){

result = result - 8;

value2 = 0;

setColor(decimal_card, 0);

setValue(txt_box_no, 0);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card3" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="1"){

value3 = 4;

result = result + value3;

setColor(decimal_card, 1);

setValue(txt_box_no, 1);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card3" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="0"){

value3 = 0;

result = result - 4;

setColor(decimal_card, 0);

setValue(txt_box_no, 0);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card4" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="1"){

value4 = 2;

result = result + value4;

setColor(decimal_card, 1);

setValue(txt_box_no, 1);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card4" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="0"){

value4 = 0;

result = result - 2;

setColor(decimal_card, 0);

setValue(txt_box_no, 0);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card5" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="1"){

value5 = 1;

result = result + value5;

setColor(decimal_card, 1);

setValue(txt_box_no, 1);

}

else if(clicked_id ==="card5" && Button_id.innerHTML ==="0"){

value5 = 0;

result = result - 1;

setColor(decimal_card, 0);

setValue(txt_box_no, 0);

}

document.getElementById("Result_of_binary").innerHTML = result;

document.getElementById("box6").value = result;

}

</script>

<h3>The decimal equivalent is: <span id="Result_of_binary"></span></h3>

</body>

</html>